Experienced researchers describe how to collaborate with practitioners on research — and publish the results.

Researchers are used to collaborating. But working with practitioners on research — and publishing the results — can pose unfamiliar challenges.

At the 2017 Academy of Management Meeting, a panel of experienced researchers shared their insights into effective research co-creation. [1]

They cautioned that one must manage practitioner expectations during the project, and reviewer expectations afterwards. The rewards, they said, are great: co-created research leads to unique insights and impacts.

Researchers on the panel were Jean Bartunek (Boston College), Jason Jay (MIT Sloan), Majken Schultz (Copenhagen Business School), and Jane McKenzie (Henley Business School). Journal editors joined them on the panel: see editors’ advice on publishing co-created research.

Co-creation Takes Many Forms

Each researcher had a slightly different take on co-creation. “There are many ways academics and practitioners can collaborate,” said Bartunek.

On the panel, Bartunek described her insider-outsider methodology, where academics and members of the organization under study work as co-researchers. “Many of these [projects] were action research, but not all,” she said. Jay calls his work action research. He periodically shared findings with the managers he studied, leading to changes in the organization’s (and project’s) trajectory. Schultz described engaged scholarship, structured so that “practitioners engage in framing issues and theoretical development of insights.” McKenzie has collaborated with practitioners in multiple ways and now focuses on action research.

How to Collaborate with Practitioners

Working with practitioners requires a different take on the research question, project outputs, and collaborator expectations. Panelists made these recommendations.

-

Develop a question relevant to academics and practitioners

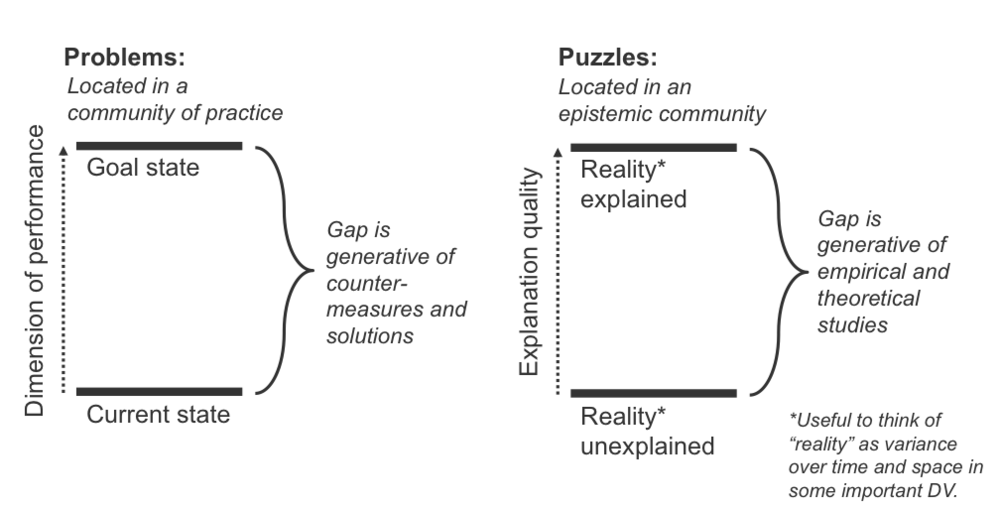

Jay recommended starting a research project by looking through two lenses. He considers both (a) a problem in a community of practice and (b) a theoretical puzzle located in academic knowledge.

Jay explained: “A problem is a gap between some current state and some goals that the organization is trying to reach. A puzzle is a gap between some sort of unexplained reality and explained reality.

“Considering both these gaps together is what’s really generative of the good solutions and inventions on the problem side. And good empirical or theoretical studies on the puzzle side.”

In planning his research, Jay lists problem and puzzle and identifies their relationship in order to find a question that bridges research and practice. For example, in his 2013 study of hybrid organizations:

-

The practical problem was that greenhouse gas emissions in Cambridge, MA were higher than targets. In response, the Cambridge Energy Alliance (CEA) formed.

-

The theoretical puzzle was why some hybrid organizations such as CEA succeed and others fail.

-

Jay drew on the idea of navigating paradox to explain the puzzle. He notes that paradox also has implications for hybrid organizations’ performance – the practical problem.

Figure 1. Jason Jay’s analysis of problem and puzzle

2. Provide valuable results to practitioner colleagues

Researchers and practitioners work on different time frames and toward different outputs. Academic papers progress slowly and often don’t address practitioner concerns.

Schultz found that her main company contact found it hard to justify the amount of time she spent with Schultz’s team. Schultz and her team had to find “ways to make this academic research interesting to the company,” Schultz recalled. “So we embarked on a lot of workshops and seminars and feedback sessions that I probably wouldn’t have taken the time to do otherwise, but that was a very important way both for her to show the relevance of the work, and also for us to learn.”

McKenzie, similarly, tries to provide practitioner value through different outputs. “Writing for practitioners is problematic because they’re not interested in complex statistics… and they want results quickly,” she explained. Her team provides project summaries, “knowledge-in-action” leaflets, and practitioner guidance documents. In one case, “we presented the results…in animated and narrated cartoons because it was a dry subject.”

These practitioner outputs have mixed benefits for the academic work. “It helps us in terms of getting our arguments straight,” said McKenzie, “but it doesn’t help in terms of the depth of the literature that’s required, and it’s a time issue from our point of view.

3. Draw on practitioners’ expertise effectively

Schultz and Bartunek involve managers in developing ideas core to the research. Managers can engage in theoretical discussions, says Schultz. She and practitioner colleagues worked through frameworks and abstract concepts.

“I think it’s a big mistake if we think that practitioners are not capable and willing to engage in theoretical discussions, but I think it is really an important role for us to showthe relevance of that discussion,” said Schultz. As Kurt Lewin said, “there’s nothing as practical as a good theory.”

Schultz initially saw her company contact as a facilitator and key informant, via monthly interviews. However, as the project evolved over four years, so did the company contact’s role. The contact ultimately became a paper co-author and workshop co-presenter. “It was fairly late in the process that idea of being a co-author came about,” recalls Schultz, “but we felt at that time we had had so many shared reflections.”

Practitioners can help build theory if the researcher is organized and disciplined, said Bartunek. Specific questions are key. “If I say, ‘This is what I have, could you please address these issues,’ it actually works,” said Bartunek. “In my experience, some practitioners get much more reflective and they get excited because they’ve never heard a particular concept before.”

Co-creating knowledge does require practitioners who are educated and curious, said Bartunek and Schultz. You need “one or two people in the company that really have a passion for research,” said Schultz.

An additional challenge: Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) can make it hard to share information. Bartunek noted that IRBs “now require insider co-authors (practitioners) to have Human Participants Review training. IRBs are also much pickier about allowing insider co-authors to see materials I have collected, for example through interviews. This makes it much more challenging truly to collaborate.”

How to Publish Co-created Research

Publishing co-created research requires managing reviewer and editor concerns.

Researchers engaged in co-creation often hear the same doubts. Some reviewers ask whether practitioners are reliable as collaborators. Will practitioners bias or censor the data?

Bartunek described reviewers asking: “Can we really expect organizational insiders to collect valid data, or are they going to twist it around? Aren’t they so engaged with it that they aren’t going to be totally truthful? Aren’t the practitioners going to get defensive if an article that’s being written is not very laudatory of them?”

However, Schultz said that in her experience, such concerns are overblown. “I’ve never been censored [by companies studied], I’ve never had any changes in my academic papers, and I think the main reason is that time passes and once we get out to publish talking about these companies, [the events are] long gone and if anything it is a curiosity about something that the past management did.”

Reviewers and editors may also voice a broader critique of action research as diverging from an objective, positivist paradigm. Editors on the panel discussed this critique as well.

That objective paradigm is a misconception, said Jay.

“One of the things that we’re taught at MIT, coming from Ed Schein, is that every project has an action research component to it, but no one talks about it or acknowledges it. You can’t be in an organization without influencing it in some way. We just have to document it and be really transparent about those methods.”

Finally, Seek Out Support

Co-creation is still a relatively novel research approach. Panelists spoke appreciatively of academic workplaces that value such practitioner collaboration. “MIT is a very engaged place,” Jay said. Schultz spoke of a “long, long tradition for working with practice” at Copenhagen Business School. At Henley Business School, said McKenzie, “it’s an ethos within the school that it matters what academics do and that it will transfer into practice.”

If the researchers do not find such support within their own institutions, they can seek a supportive community outside. Panelists suggested workshops in academic conferences and connecting with individuals who have successfully conducted and published co-created research.

Find Out More

Bridging research and practice is core to the NBS mission.

Explore our recent resources for researchers interested in collaborating with practitioners.

And, join us as a contributor to the resources we are developing. Please share your interest by emailing Garima Sharma.

[1] We use the word co-creation to include methodologies such as action research, insider-outsider research and engaged scholarship that involve practitioners as knowledge partners

NBS’s Co-Creation Initiative

NBS seeks to help researchers navigate the path of co-creation with practitioners: integrating academic and practitioner knowledge for unique insights. Review our many existing resources and subscribe to our academic newsletter for new co-creation guidance.

We also hope you’ll contribute your own insights. Please share your interest by emailing Garima Sharma.

Add a Comment

This site uses User Verification plugin to reduce spam. See how your comment data is processed.This site uses User Verification plugin to reduce spam. See how your comment data is processed.