Technology such as blockchain can make the mining industry more sustainable, but supplier engagement is still crucial. The cobalt supply chain provides lessons.

It might seem ironic, but sustainable development relies on the mining industry. The industry provides the metals and minerals necessary for technological and sustainable advancement. These materials enable sustainable innovations such as electric battery vehicles (EBVs) and solar panels.

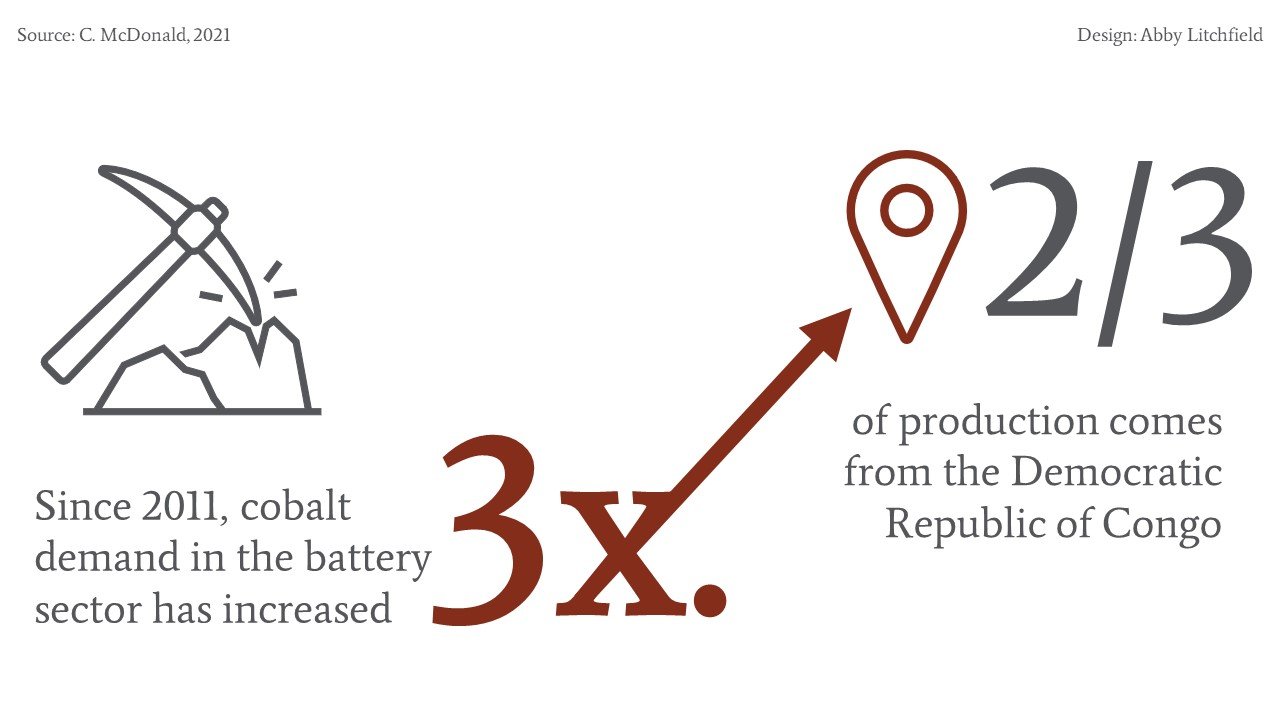

Cobalt is particularly important to the sustainable development transition. Cobalt’s ability to deliver unparalleled performance in lithium-ion batteries, has made it the mineral of choice for EBV manufacturers. It is also a key component in the lithium-ion batteries in laptops, mobile phones and other technological devices. Between 2011 and 2018, demand for cobalt in the battery sector tripled.

Despite cobalt’s crucial role in sustainable development, its supply chain faces many social and environmental challenges. Over ten months, I studied how environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria could be improved within the cobalt supply chain, and whether blockchain technology could help.

My research findings from the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Africa and Switzerland show the importance of greater transparency through blockchain technology as well as stakeholder — especially supplier — development. These lessons can provide insights for others looking to improve sustainability within the mining industry.

Cobalt comes from a country in transition

Today, approximately two-thirds of the world’s cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), a country gradually recovering from decades of war and social, political and economic turmoil. In the coming years, the DRC is expected to provide three-quarters of the total global cobalt supply .

In the DRC, cobalt’s impact is complicated. Cobalt is extracted through large-scale or industrial mining by large multinational companies, as well as through artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM)[1]. Labour-intensive and low-tech, ASM accounts for 15-30% of the cobalt ore extracted from the DRC. These subsistence miners provide valued local income, in a country where approximately 73% of the population lives below the international poverty line.

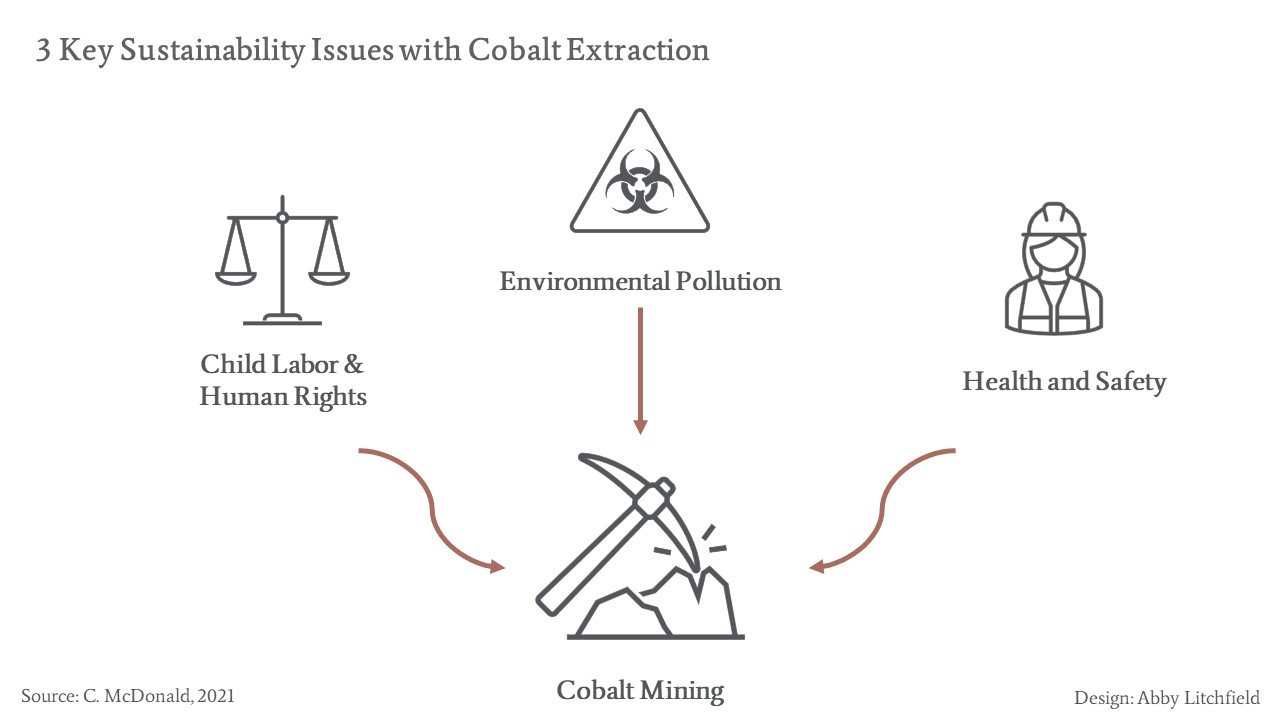

Yet cobalt mining can also have devastating social and environmental impacts, particularly at ASM sites. Child labour, human rights abuses, environmental damage and health and safety violations have all been widely documented within the industry.

Increased attention has led to calls for action

In 2016, Amnesty International released “This Is What We Die For,” a report detailing how cobalt from ASM sites in the DRC entered the supply chains of multinational companies. The report named and shamed actors, identifying child labour and human rights abuse within the supply chains of Apple, Samsung, and others.

The report provoked widespread alarm and public scrutiny, drawing attention to conflict minerals and the lack of oversight within mineral and metal supply chains. Legal action and more NGO reports have brought further attention to the need for greater transparency and traceability across the cobalt supply chain.

Many companies have disengaged from ASM sourcing, while others have joined efforts by the DRC government and the OECD to “formalize” or regulate the industry. Several countries have also become increasingly concerned, with legislation passed recently on supply chain management and conflict minerals in multiple countries.

But have these efforts really had an impact on the ground? Three years after the release of Amnesty International’s 2016 report, I travelled to Kolwezi, DRC, to visit cobalt mining sites and see firsthand what the implications were for ASM and the cobalt industry.

Is the cobalt supply chain becoming more sustainable?

In the DRC, I spoke with and surveyed artisanal miners, CSR managers and consultants. Based on my findings and other research, limited change has occurred within the cobalt supply chain. Severe environmental pollution continues to affect both workers and local communities. Human rights violations still occur and child labour remains, although it’s less widespread. Several mining companies have tried to integrate health and safety measures at their sites; however, implementation varies due to funding constraints and limited training.

To understand potential sustainability-focused solutions, I interviewed 36 stakeholders in Switzerland and South Africa. They represented investors, commodity traders, civil society actors, blockchain practitioners and stock exchange employees.

My finding: Key actors, including large mining multinationals, commodity trading companies and consultancy firms, increasingly emphasize technological solutions to cobalt’s sustainability challenges. In particular, they see blockchain as a way to increase transparency and traceability within the cobalt supply chain.

Yet my insights from on the ground in the DRC point to a more complex solution. Blockchain won’t resolve the problem without supplier development and engagement – the fundamentals of sustainable supply chain management.

Blockchain can improve supply chain transparency

Blockchain technology can provide a secure, traceable and transparent way to store and share information in a network. “Blocks” of data are stored in an unchangeable digital “chain,” within a system called distributed ledger technology.

To trace a bag of cobalt, a block of information can be added at each step of the supply chain, through a unique identifier, such as a QR code. Metals and minerals can also be traced using information on their chemical composition or by a unique mark or tag.

Often, supply chains provide little documentation of potential sustainability issues. Purchasers may not have information on the conditions under which the good was produced or on second or third tier suppliers.

By contrast, the blockchain approach verifies information up front. A new “block” of information can only be added with the approval of a majority of network members. Information can’t be changed once it’s added, and all members of the network can access the information.

The result is a system that can provide unparalleled visibility into every step of a product’s journey, from extraction of the mined cobalt to battery creation.

Many companies, including Trafigura, IBM, Ford and Tesla, have already begun to adopt blockchain technology, with the aim of improving the transparency and traceability of cobalt within their supply chains.

Supplier development remains essential

Blockchain can help managers gain better oversight of the supply chain, by connecting cobalt to its source. It can also help downstream actors be more aware of the relevant social, environmental and health and safety issues when making purchasing or investment decisions.

However, I argue that blockchain technology should be considered a helpful addition to resolving supply chain concerns, rather than a complete solution.

Through multiple site visits and surveys in the DRC, it became clear that not even a technology as innovative as blockchain would be able to solve the issues on the ground. Blockchain has significant benefits when it comes to transparency and traceability, but it should be viewed as a tool to help support on-the-ground change. That change requires direct interaction with suppliers and communities.

The following three principles can help managers in the cobalt industry and in the extractive sector more broadly, support such real-world change:

1) Accurate and transparent data collection (even in analog form)

Blockchain can provide a more efficient way of storing information, but it doesn’t address how the data is initially collected. Many experts expressed concern around data collection methods, noting that “garbage in” results in “garbage out.” Setting clear expectations and processes for data collection can reduce this issue and further improve transparency.

2) Continuous engagement across the supply chain

Blockchain can provide information about sustainability risks and where in the supply chain they occur. Then companies need to act in order to fix and reduce these problems. Child labour, for example, can’t be eliminated solely through the implementation of blockchain technology within a mining company’s supply chain.

Companies should engage with suppliers at all levels, starting with artisanal miners, to better understand on the ground needs and address root causes. For example, providing appropriate protection and income security for workers can go a long way in addressing the root causes of child labour, such as poverty and the inadequate wages and conditions faced by adult miners.

3) Long-term horizons, to bolster trust and improve conditions over time

Companies should take a long-term perspective and engage continuously with suppliers, as they transition to more sustainable modes of production. Although once a common practice within the extractives industry, disengagement at first fault should be avoided: this only pushes local miners outside of regulated areas and amplifies issues. Engaging on longer term horizons instead can bolster trust between parties and allow for continuous improvement over time.

Focus on sustainable development

Cobalt’s sustainability challenges are often in the spotlight, but there are also lessons to be learned more broadly for the mining industry – a vital but challenging economic sector. Whether it’s gold, tin, tantalum or tungsten, many other metals and minerals encounter environmental and social issues, as well as difficulty with transparency.

Sustainable development is beginning to be understood beyond economic growth and technological advancement, to account for issues of social justice, environmental stewardship and governance.

The cobalt industry represents a sector of great potential for sustainable and technological advancement. However, given its complex supply chain, it remains critical that technology is not be viewed as a solution in itself, but rather as an additional tool to support capacity development and trust building across the supply chain.

[1] Artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) is defined as “formal or informal mining operations with predominantly simplified forms of exploration, extraction, processing and transportation. ASM is normally low capital intensive and uses high labour-intensive technology” (OECD Due Diligence Guidelines, 2016).

Additional Resources

- Amnesty International. 2016. This is what we die for: Human rights abuses in the Democratic Republic of the Congo power the global trade in cobalt.

- Azevedo, M., et al. 2018. Lithium and cobalt – a tale of two commodities. McKinsey & Co.

- Banza Lubaba Nkulu, C., et al. 2018. Sustainability of artisanal mining of cobalt in DR Congo. Nature Sustainability, 1: 495-504.

- Baumann-Pauly, D., et al. 2020. Making mining safe and fair: Artisanal cobalt extraction in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. World Economic Forum.

- Calvao, F., McDonald, C., & Bolay, M. 2021. Cobalt mining and the corporate outsourcing of responsibility in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The Extractive Industries and Society, 8(4).

- IBM. 2019. What is blockchain?

- International Finance Cooperation. 2017. Blockchain: Opportunities for private enterprises in emerging markets.

- Tsurukawa, N., Prakash, S., & Manhart, A. 2011. Social impacts of artisanal cobalt mining in Katanga, Democratic Republic of Congo. Öko-Institut e.V.

- van der Merwe, Antoinette. 2020. A blockchain is only as strong as its weakest link: Transparency and artisanal gold.” ETH Zürich & NADEL.

- The World Bank. 2021. The World Bank in DRC.

Add a Comment

This site uses User Verification plugin to reduce spam. See how your comment data is processed.This site uses User Verification plugin to reduce spam. See how your comment data is processed.