50 researchers share their experiences translating research for practitioners. Use this crowd-sourced wisdom to bring your research to people who can use it.

Translating research for practice — bringing academic insights to managers and other users — can seem simple. But, like any skill, it must be learned. Fortunately, others are glad to share their experiences.

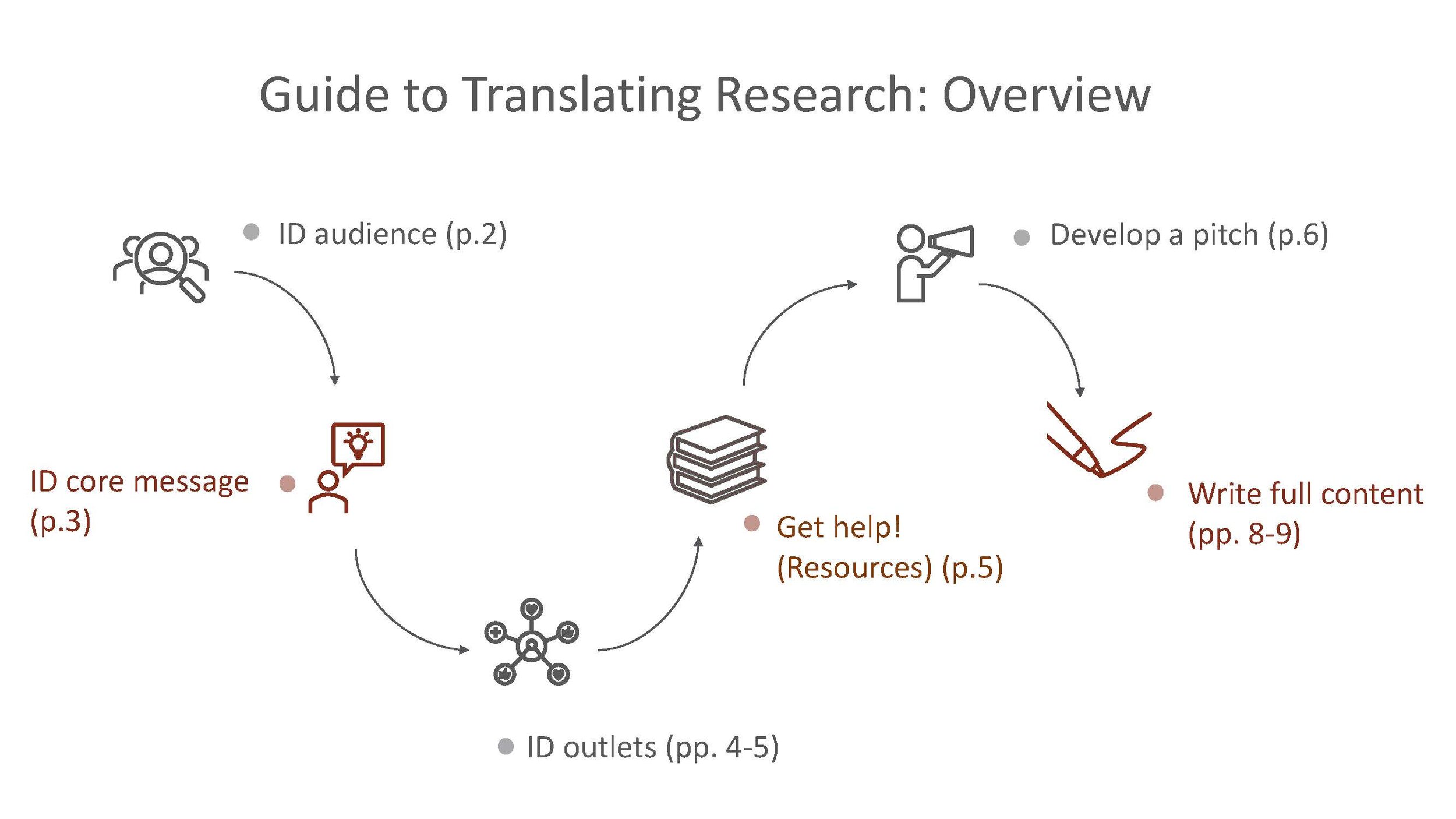

This article is the third in a series of articles on research translation. Previously, we wrote about translating research without removing abstraction, and presented NBS’s step-by-step Guide to Translating Research.

This article draws on the wisdom of the (researcher) crowd. In collaboration with the Impact Scholar Community, NBS surveyed researchers on their experiences with research translation. More than 50 people provided resources, reflection, and advice.

Some researchers are lucky enough to have a university media team that can help with the translation process. But understanding the basics can facilitate your work with media staff and give you independence and flexibility.

We present survey insights following the structure of the NBS Guide to Translating Research, integrating some content from that document as well.

Design by Abby Litchfield

Step 1: Identify Your Audience

Who would benefit from your research discoveries? Ideally, you identify relevant audiences early in your project, as knowing potential users can help you refine your research question.

In identifying an audience, be as specific as possible. Our survey found that “business leaders” were the most popular audience (42/50 responses) followed by “government” and “general public.” But these are large categories. What kind of business leader or manager will find your research insights useful? Supply chain managers, human resources professional, and bank CEOs may have different needs.

Step 2: Identify Your Core Message

With your audience in mind, identify your most relevant insights. What might your audience want to know, based on your understanding of their resources and challenges?

Note that while researchers are trained to describe phenomena, managers often seek recommendations for action. Emphasize practical take homes and guidance without losing the complexity of your insights or straying too far from your data.

Respondents to our survey shared these ideas about crafting a core message:

“Practitioners take for granted that we did the ‘due diligence’ of rigor, and they just want the results. And those results put in their context, with practical, concrete implications.” – Adrián Zicari, ESSEC

“Exploratory, qualitative, or descriptive research contributes to theory but doesn’t always yield immediate and clear insights for practice. This makes it difficult to translate this type of work to a business audience.” – Merriam Haffar, University of Michigan alumna

“Translate abstract concepts into the ‘language’ of the people you want to benefit with your work. They need to make sense of what you do to help you develop the ‘solution’ and apply it to their context….Abstract concepts are always just a guiding lens, not a final solution.” – Esther Hennchen, University College Dublin

Step 3: Identify Outlets to Reach the Audience

What outlets and formats will reach your desired audience? For business audiences, useful outlets may include industry and professional associations and practitioner-oriented journals and conference. The Conversation can be a great way to reach the general public. The Web has many targeted newsletters and platforms. And social media is also a powerful tool.

Respondents to our survey shared these ideas about effective outlets and formats:

“Ask to moderate sessions in practitioner conferences on your themes. Ask to be part of expert networks. Send your reports to governmental officials. I always think: 1 paper, 1 case study (for pedagogy), 1 report (or 1 article for media). It does not always happen but I try.” – Delphine Gibassier, Audencia Business School

“Always prepare PPTs in English and the language of the population who participated in the research. Plan for technical reports, manuals, catalogue-like “light” publications, flyers, YouTube videos etc.” – Ieva Zebryte, Universidad de La Frontera/ ISM University of Management and Economics

“In my research team, we usually prepare reports with a summary of main findings of the research, and then we send this report to practitioners that have participated in the study. We research mainly in the hotel industry and we also send the reports to professional associations in this industry.” – Jose Molina, University of Alicante

“Reflect on your strengths, the skills you wish to develop, the networks you wish to contribute to, and the impact you wish to make in order to focus the means by which you translate your research. It may not make sense to invest time and effort into something that you do not feel good at or do not enjoy. I have found success in podcasting, and using a social media scheduler to develop a communication calendar to translate my research outputs.” — Steven Curtis, Lund University

On the survey, we asked individuals to rank different research translation channels. Here’s the order, from those viewed as most impactful to those viewed as least impactful: (1) media outlets (e.g. Harvard Business Review, general media), (2) in-person events (e.g. corporate conferences) (3) university communications (e.g. social media and web), (4) personal outreach (e.g. social media).

Step 4: Access Resources for Research Translation (If Possible)

You are not alone! Even if your university doesn’t have its own media staff, you can likely find others to help you on the translation journey.

In particular, draw on friends and family outside academia for feedback on your communications. Linguist Jeffrey Punske calls this approach the “Grandma Test”: describing your work to someone completely outside your field as a way to identify jargon.

Survey respondents shared these ideas on possible resources:

“You can start small to test your translation (family, practitioners who partner up with your university…) both orally (presentation) and written (e.g. blog post).” – Frederic Dufays, KU Leuven

“Former students or colleagues who are currently working outside academia but are interested in staying connected with your university/department are a great resource.” – Heather Schoonover, Lund University

“I engage undergraduate and graduate students in all of my research so that they can follow up by doing the translation of research into practice.” – Ieva Zebryte, Universidad de La Frontera/ ISM University of Management and Economics

“Encourage faculty to include knowledge management strategies in grant proposals and budgets” – Anonymous

Access additional guidance (multiple suggestions): Responsible Research in Business and Management, Integration and Implementation Sciences Network, On Writing Well, LSE Impact Blog

Step 5: Craft a “Pitch”

Often, translation will involve an initial contact with gatekeepers or intermediaries (journalists, conference organizers), before you engage your desired audience. For them, you’ll develop a “pitch”: a short statement of what you have to offer that will encourage those intermediaries to ask you for more.

For the pitch, write a headline and a few supporting paragraphs. The headline should be less than 10 words and emphasize relevant keywords: e.g., what someone might type into a Google search. An example might be: “How to Motivate People Toward Sustainability.”

In supporting paragraphs, briefly identify your topic, why it matters, and your evidence base. (More guidance on pitch development is available in an NBS conversation with editors from Harvard Business Review and The Conversation.)

Keep reflecting: why would a busy manager, oriented toward action, pause and read what you’ve written? What is the practical puzzle that your research is solving?

Step 6: Develop Full Content

Communicating with practitioners requires that we keep our insights short, clear, and engaging. We have to unlearn or at least momentarily suspend the language of academia and use language that is accessible to all. For engagement, starting with a question or a story can be a useful hook.

Survey respondents shared these ideas on communicating with practitioners:

“Don’t use jargon or long, complex sentences or paragraphs. Practitioners like anecdotes and stories that breath[e] life into research findings….You have to speak differently (have a different writing voice) when writing for popular or business audiences. Academic voice will ensure no readers. Read a bit on copywriting—i.e. marketing writing. It is needed to ‘hook’ casual readers.” – Kevin Taylor, Stetson University

“[Move] beyond statistical analysis results, to focus on the real meaning of results.” – Rosa Maria Dangelico, Sapienza University of Rome

“Use stats on pervasiveness of idea(s) for their business success (or agency success, or organization’s success)” – Hildy Teegen University of S. Carolina

“I’ve found that when it comes to writing practitioner-facing articles, business audiences respond best to articles that have a clear and strong perspective.” – Merriam Haffar, University of Michigan alumna

“I use Canva for creating visually appealing graphics and presentations; Adobe Audition for recording and editing sound clips or podcasts; CoSchedule to schedule posts across social media and blogs; Pixabay, Pexels, The Noun Project for free imagery and icons” — Steven Curtis, Lund University

Always: Recognize Translation Is Only Part of Research Impact

Survey respondents emphasized that greater research impact comes from close collaboration with practitioners. Research translation is about sharing your research with practitioners, while research co-creation involves developing your research in interaction with practitioners. At NBS, we have often engaged academics and managers in such co-creation. These efforts are more resource-intensive than translation but can result in powerful insights and impact.

Additionally, focusing on how to craft insights for translation can minimize the importance of mobilization. Translation can be passive: sharing insights and hoping that someone uses them. Truly getting your ideas into use is an active exercise that requires partnering. For example, managers may be willing to use the research insights if they hear about them from their peers at an industry conference.

Mobilizing requires participating in public discourse — engaging in open conversation about ideas. Note that often you’ll be drawing on insights not only from a specific project but from your research agenda and beyond.

Survey respondents shared these ideas on learning from, and working with, practitioners:

“Qualitative and longitudinal research projects are a perfect way to build relationships that last and are helpful both for research and for impact.” – Giuseppe Delmestri, WU Vienna

“Co-design, co-production and co-interpretation/implementation are key to impact, so interactive engagement throughout is needed, e.g. workshops are an important vehicle.” – Stefan Kaufman, Founder, Waste and Circular Economy Collaboration at BehaviourWorks Australia, Monash University

“Keep in mind that as a social scientist you are not so much “creating knowledge” as asking participants to share their knowledge, and then reassembling it to create something new. Much of the knowledge we are ‘translating’ was their knowledge in the first place” – Alice Palmer, consultant

“[When participating in a podcast], the thing that helped me was to frame my role not as the definitive expert or solution-giver but as someone who can help dispel certain stereotypes, question assumptions, bring nuance to a politicized issue.” – Nevena Radoynovska, Emlyon Business School

More about the Survey Respondents

Here’s a bit more about the individuals who responded to the survey. We received 47 responses, from researchers in 19 countries.

Career stage: 40% are PhD students or postdocs, 21% are assistant professors or lecturers, 17% are associate professors or senior lecturers, 17% are professors, and 4% are consultants.

Experience with research translation: 47% had less than 2 years of experience, 28% had 2-5 years of experience, and 26% had more than 5 years.

Success in research translation: 9% saw themselves as successful or very successful, 66% saw themselves as somewhat successful, and 26% saw themselves as not successful at all.

Time spent on research translation: 32% of respondents spent less than 10% of their time on research translation, 45% of respondents spent 10-25% of their time, and 23% of respondents spent more than 25% of time.

Sequence for considering translation: Individuals thought about translation before starting a research project (57%), while conducting the research project (66%), and after completing the research project (60%). (Multiple answers possible.)

Share Your Ideas on Research Translation

What do research translation and impact mean to you? Share your ideas in the comment section. And, please consider working with both organizations behind this survey:

NBS always welcomes your content ideas (submit them online) and reflections on co-creation (write to Garima Sharma, gsharma7@gsu.edu).

The Impact Scholar Community is a community for early-career research scholars who want to connect research to impact. Find out more and join.

Add a Comment

This site uses User Verification plugin to reduce spam. See how your comment data is processed.This site uses User Verification plugin to reduce spam. See how your comment data is processed.