The circular economy takes a special form in low-income settings. It’s driven by individuals and emphasizes labour and resourcefulness over technological solutions. Its implementation has lessons for all.

The circular economy aims to reduce waste by rethinking every aspect of a product’s life cycle. Strategies like redesign, repair, and reuse extend product life and reduce the need for raw materials.

Descriptions of the circular economy often focus on technologies and approaches from wealthier settings – like the “Global North.” But researchers have recently looked instead at the circular economy in low-income communities.

Researchers Angelina Korsunova, Minna Halme, Arno Kourula, Jarkko Levänen, and Maria Lima-Toivanen examined poor urban areas in Tanzania, Brazil, and India. There, they found a different kind of circular economy. It emphasizes labor and resourcefulness (“making do”) over efficiency and technological solutions. It offers lessons for everyone interested in circular approaches.

A Tale of Two Circular Economies: In High-Income and Low-Income Settings

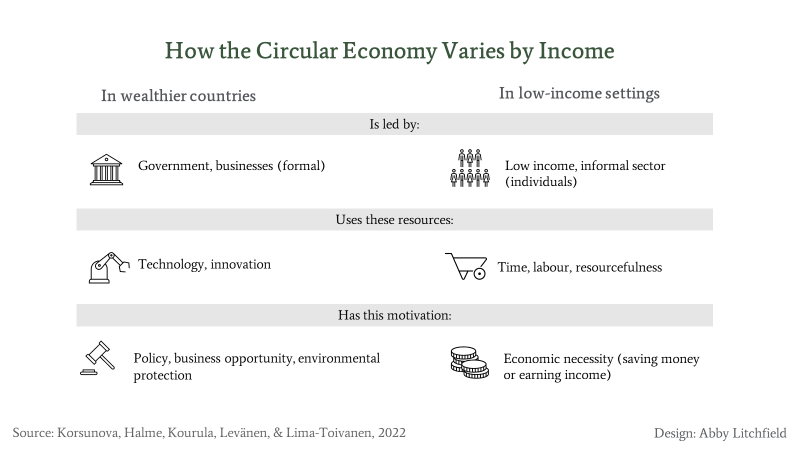

The graphic shows how the circular economy differs in wealthy and lower-income communities.

The Circular Economy in Wealthier Countries

In wealthier countries, the circular economy is led by government and business.

-

-

Government sets formal policies that guide the circular economy: for example, recyclability and safety standards that affect the reuse of materials, subsidies, roadmaps and networks to encourage action. International agreements may also emphasize circularity as a path to environmental protection.

-

-

-

Businesses develop technological innovations that will enable them to incorporate circular strategies. For example, Fairphone has redesigned phones to make components easy to replace. Businesses may be affected by policy directives or market forces, from material scarcity to consumer interest.

-

The Circular Economy in Lower-Income Settings

The researchers studied everyday practices in poor urban areas of Tanzania, Brazil, and India [1]. They found the circular economy to be powered by the “informal sector,” which means workers without formal contracts or government regulations. Very small businesses and entrepreneurial individuals are at the core of the local circular economy.

That fits with broader economic patterns in developing countries, where about half of economic output comes from the informal sector. These workers tend to be poor. They are using circular strategies — repairing, reusing, and recycling goods — in order to save money and get income. They’re not motivated by policy incentives or environmental concerns. Instead, they’re “making do” – using whatever is available. It’s the “necessity-driven circular economy,” the researchers explained.

Here are some of the CE practices that you might see in these locations.

Reuse & Repurpose

Individuals wash plastic and metal containers and then reuse them for carrying/storing water, liquids, grains, or charcoal. In Tanzania, the reuse of plastic buckets is so widespread that buckets have become a standard measure in the sale of flour, cereals, etc.

There are hundreds of “micro-businesses” that either specialize in making different household items or agricultural tools out of recycled materials, or simply sell pieces of wood and metal scrap for similar purposes. Simple ovens are made out of barrels, and water containers are made from regular plastic containers by adding a nozzle.

In Brazil, it’s common to repurpose plastic bags as storage solutions in low-income households, to keep goods off the floor. In India and Tanzania, newspapers have a long life, as packaging in markets or even as food serving cups. Once used, they are burned as fuel in cooking.

Repair

Repair services were readily available in all the low-income locations, located close to markets and other busy areas or based out of people’s homes. They repair shoes, furniture, clothing, and electronics. Low labor costs make it cheaper to repair rather than buy new.

Recycle

Informal recycling is also called “waste picking.” Waste pickers collect valuable recyclables like paper or metal from private households and from the roadside. They may work with others: In Belo Horizonte, Brazil, waste-pickers had a cooperative that helped them organize storage for collected recyclables and transport materials to the municipal recycling facilities. In Kanpur, India, waste pickers sell to middlemen who then resell the materials and act as brokers in the materials market.

Recognizing the Value of the Low-Income Circular Economy

The work done by the informal sector in the circular economy has real value for society and individuals.

In low-income contexts, municipal solid waste recycling is largely managed by the informal sector, according to studies from China, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Indonesia. These workers have special skills and local knowledge. For example, many waste buyers have well-established “routes” in the narrow streets of low-income urban areas. That allows them to be more efficient in waste collection than municipal authorities. As another example, repairmen are resourceful in their work, using a wide array of scraps and materials to quickly make goods functional again.

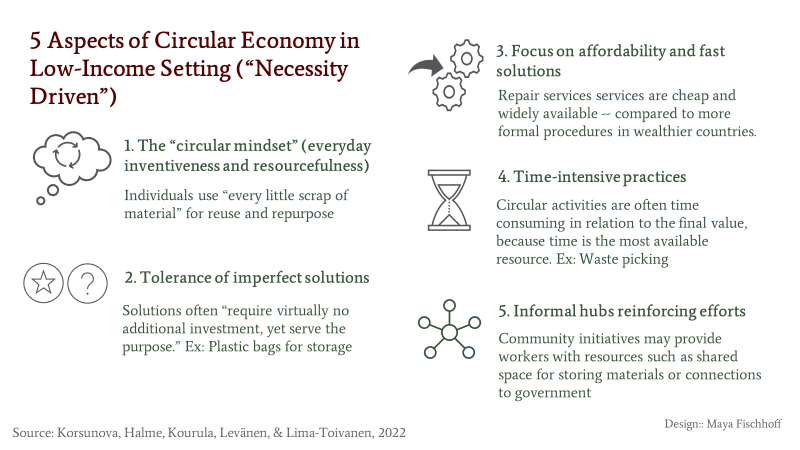

The researchers identified 5 special characteristics of the necessity-driven circular economy that make it different from formal circularity in wealthier settings.

-

-

The “circular mindset” (everyday inventiveness and resourcefulness). “In India and Tanzania every little scrap of material is salvaged for reuse and repurpose,” the researchers wrote. “Even small pieces of fabrics are used for making protective boundaries around flower beds.”

-

Tolerance towards imperfect solutions. Plastic bags aren’t perfect for storage – but they work. In Tanzania, car tires make benches for community “meeting places”. “All these require virtually no additional investment, yet serve the purpose,” wrote the researchers. This is “making do.”

-

Focus on affordability and rapid solutions. People value quick and affordable solutions that make goods functional again. This is why roadside repair services are widely available, affordable and inventive in the way they work. Wealthier settings, by contrast, emphasize established procedures: for example, authorized (and slower) repair services.

-

Engagement in time-intensive practices. Many of these activities are time-consuming in relation to their final value. Waste-picking activities typically take days for relatively little money. But in low-income contexts, time is often the most readily available resource.

-

Informal hubs reinforcing the circular economy. Some relatively informal organizations help people participating in the informal economy. These might be informal cooperatives or local community initiatives. They provide workers with resources such as shared spaces for storing materials or connections to city waste management services.

-

Lessons for the Circular Economy Across the Globe

It’s clear that the circular economy looks different in poorer settings than in wealthier ones. And that makes sense, Korsunova and colleagues say. Approaches are more likely to be successful when they are firmly rooted in a specific context or setting. The way the circular economy has developed in low-income settings makes sense given the local environment: thrifty households, lively markets for used materials, and individuals with waste recovery skills and access to customers.

Lessons for the circular economy in wealthier settings

Radical innovations for advancing circularity can come from when we learn from this resourcefulness, affordability and tolerance towards imperfect solutions, Korsunova told NBS. “Instead of focusing on minor efficiency gains in processes still powered by primary materials, businesses in the wealthier settings could innovate local solutions with “make-do” resources,” she said.

For example: The founder of Scottish company MacRebur was inspired by seeing low-income individuals in India setting aside waste plastic to burn and melt it in the potholes on the road, as a makeshift solution for repairing the roads. Thus a business mixing waste plastic with other materials for paving roads was born in Scotland.

Businesses can use the framework of the five special characteristics of necessity-driven CE to drive business imagination beyond the usual boundaries and open up new opportunities. Unconventional thinking, shifting away from established ways and procedures, can help them draw on seemingly low-value waste, make use of local skills or expertise, and find benefits for local communities. “One of the main lessons of necessity-driven CE is about learning to creatively “make do” with what is already there,” said Korsunova. That leads to envisioning and creating a local circular economy.

Recommendations for the low-income circular economy

There are also ways to make the low-income circular economy stronger. That can happen by building on what individuals have already developed. “Instead of trying to leapfrog to the waste management systems of developed countries, the focus should be turned to the question of how to enhance locally-tailored broader CE systems,” the researchers write. That means supporting existing practices that emphasize the skills of low-income individuals, while improving their safety and wellbeing.

Despite their valuable contributions, these individuals often face hardships and injustices. They make little money, can be exposed to harmful substances, and often experience discrimination even arrest. “The police used to treat us like bandits,” one waste picker commented.

As many cities turn more attention to their waste management, they would do well to integrate existing local practices with new technologies, the researchers say. That approach can harness the full potential of circularity, both formal and informal. By contrast, when new systems and technology have displaced the existing informal workers, local opposition and unrest have arisen.

The researchers recommend these actions for government and businesses:

-

-

Legalize and integrate informal circular economy jobs. Cities could make these activities part of formal waste management, providing more stable income.

-

-

-

Connect informal repair services to business products, for example by integrating them into existing authorized repair networks.

-

-

-

Reduce stigma and increase safety. Waste pickers need access to supplies like safety gloves and health services; this could happen by making them part of municipal waste management.

-

-

-

Support institutions like cooperatives and hubs that aid these workers.

-

Learning from Each Other on the Circular Economy

There’s inspiration for everyone in the solutions and resourcefulness on display. In Brazil, Tanzania, and India, the researchers saw an oven made out of a barrel; fish coolers made from cardboard, plastic, and ice; and PET bottles used for plant pots or to protect toothbrushes. Korsunova told NBS: “The simple low-tech solutions can spark ideas and energize us all to value, respect and engage with what we already have at our hands. This informal circular economy can energize us all.”

[1] More about the research methods: The researchers studied the urban areas of Belo Horizonte in Brazil, Kanpur in India, and Dar es Salaam in Tanzania. These locations were selected because they were cities with significant low-income populations where people live on less than the equivalent of 5 euros a day. The researchers and local collaborators conducted interviews and observed in locations including recycling stations, slums, markets, shops, factories, households, and schools – aiming to understand the circularity practices they saw.

Find Out More

The original article:

Korsunova et al. 2022. Necessity-driven circular economy in low-income contexts: how informal sector practices retain value for circularity. Global Environmental Change, 76.

NBS resources on the circular economy:

Kim, H. 2021. What is a circular economy and how does it work?

Patala, S. 2019. How to accelerate the circular economy.

Why We Wrote This Article

NBS surveyed readers in January 2023 to ask about their priority business sustainability topics. People wanted to know how the circular economy varied in different settings. Here are some of the comments received:

-

-

How do you implement the circular economy in contexts where there are poverty and low development? How do you evaluate the level of implementing the circular economy?

-

-

-

In my country, Pakistan, we face a… dire need to recycle waste; for example, plastic bags may be banned as these are not environment friendly.

-

-

-

What is garbage for some is a raw material for others. No to the programming of obsolescence for any product and to consumer debauchery. In developing countries we repair everything because … it is hard for us to buy everything new.

-

To address this issue, NBS Content Committee member Samuli Patala, an expert on the circular economy, recommended this article by Angelina Korsunova and colleagues.

Add a Comment

This site uses User Verification plugin to reduce spam. See how your comment data is processed.This site uses User Verification plugin to reduce spam. See how your comment data is processed.