Indigenous insights show how to advance all forms of development, from the economic to the social. A project in Aotearoa/New Zealand shares lessons.

Leaders interested in sustainable development should look to Indigenous perspectives.

That’s because across the world, Indigenous people have distinctive ways of relating to the natural world. They see close connections between people, other beings, and the land. Here are some key sustainable ideas common to many (but not all) indigenous worldviews:

- Reciprocity. Indigenous people often see themselves as part of the environment, rather than in a position of power over nature. This leads to naturally seeing reciprocal relationships between people and the environment: each offering support and care.

- Place-based knowledge. Indigenous people often have deep knowledge about a place over time — everything from weather to plant and animal populations. That knowledge leads to more sustainable thinking, decisions and practices.

- Diverse forms of value: Indigenous people recognise many sources of value in the environment. The land provides material resources like food, but it also supports mind and spirit. The environment is valued beyond its economic benefits.

With some thought and effort, these Indigenous views, and others, can be used with Western views; Mi’kmaw Elder Albert Marshall called this approach ‘Two-Eyed Seeing.’ We believe that taking an ‘indigenous eye’ into how we view economic development may be our best hope for a sustainable future.

In this article, we describe an approach to creating a regional development strategy that meaningfully integrates community views. The process resulted in a new strategic tool as well as a specific strategy, and both build on Indigenous insights.

Are you curious about how to lead and achieve sustainable development in your organization or within your community? Are you eager to engage meaningfully with different stakeholders? We hope that this story will provide you with inspiration and concrete guidance. Here’s one key lesson: Economic development can’t be the sole driver. It must come with other kinds of resources and strengths: cultural, social, environmental, and even political. The tool we share below provides a model.

Co-creating Strategy with Māori Communities In Aotearoa/ New Zealand

We are faculty members at Te Herenga Waka – Victoria University of Wellington. One author of this article (Jesse Pirini) is Senior Lecturer in Business and Government; the other (Stephen Cummings) is Professor of Management.

We live in Aotearoa New Zealand; Aotearoa is the Māori name for our country. Māori are the indigenous people, first discovering these islands in the early 1300s. Like most indigenous peoples, Māori experienced colonization, losing geographical, political, and cultural resources from the 1800s. However, Māori continue to retain and build cultural identity, and have been driving a re-vitalisation since the 1970s. Nowadays, Māori make up 16% of the population of Aotearoa/New Zealand, and the Māori economy is valued at an estimated $NZD75 billion.

In 2019, the two of us were part of a team that won a contract to help build a Māori economic development strategy for Te Upoko o te Ika a Māui the region around Wellington in Aotearoa New Zealand. Te Upoko o te Ika a Māui, means “the head of the fish of Māui.” (In mythology, Māui caught the giant fish that is now Aotearoa’s North Island).

We recognized it was a rare opportunity. The regional Council, which commissioned the strategy, heard calls from local communities to develop a strategy ‘by Māori, for Māori.’ They supported a full community engagement process. It was a chance to open up economic development strategy in fundamental new ways: to ask local Indigenous people what they thought a strategy should look like and what it should aim to achieve.

Steps to Develop the Strategy for Sustainable Development

The project’s advisory board (called an ‘ohu’) provided us two important insights at the start:

- Go into hui (open ‘town-hall’ meetings) with a framework, but one that can be adapted. “You need some focal point or else you’ll go round in circles,” they said.

- Have the first people adapting the framework be rangatahi (youth). “Our people will respect their views, because this is for them,” the ohu said. (The Māori population is very young, with 58% under 30 years of age.)

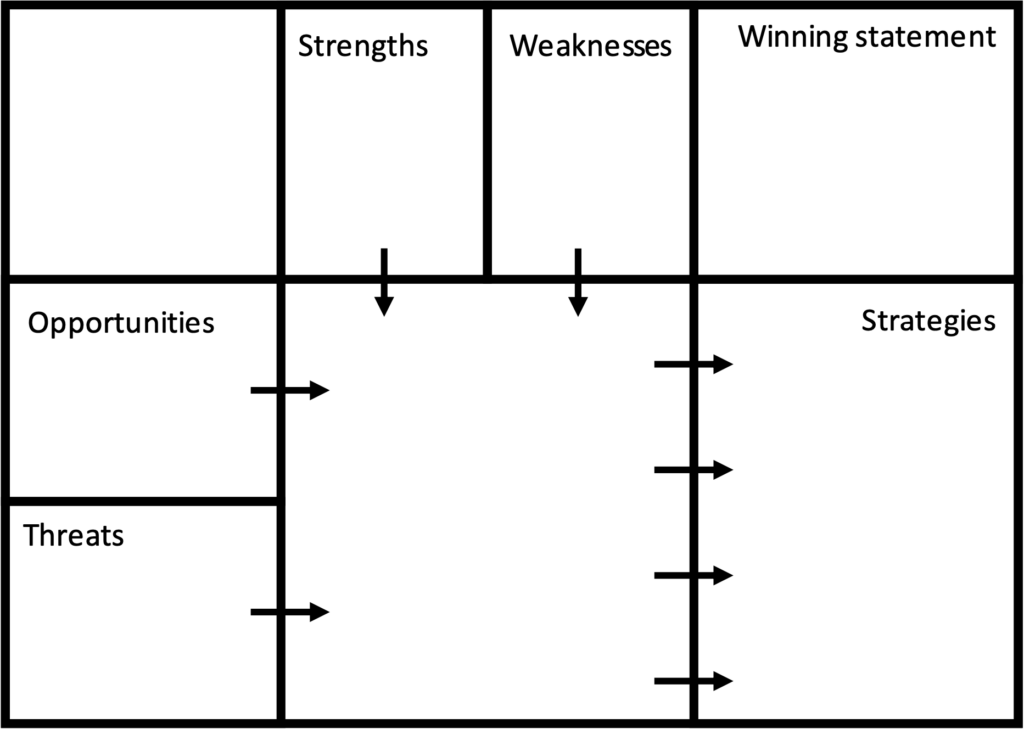

For the initial framework, we borrowed from a book by Stephen called Strategy Builder and developed a basic open strategy ‘canvas.’ (A canvas is a template or model used to develop strategic thinking). We used a simple combination of the classic Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) model, oriented toward a vision of ‘what winning looks like.’ That became our starting point.

Then, our first hui (town hall) brought together local students who began to shape the canvas toward what was important to them as young Māori. This hui led to many more. This video shows some of their reflections.

Ultimately, the process resulted in:

- The Ruruku Canvas framework for strategy development, a new strategy tool. Ruruku can mean ‘to weave together’ in the Māori language. It reflects an integrated approach.

- An economic development strategy for our region that reflects Māori world views. Using the Ruruku Canvas, community members developed this regional plan, which is now being implemented.

Key Points of the Ruruku Canvas Framework for Strategy Development

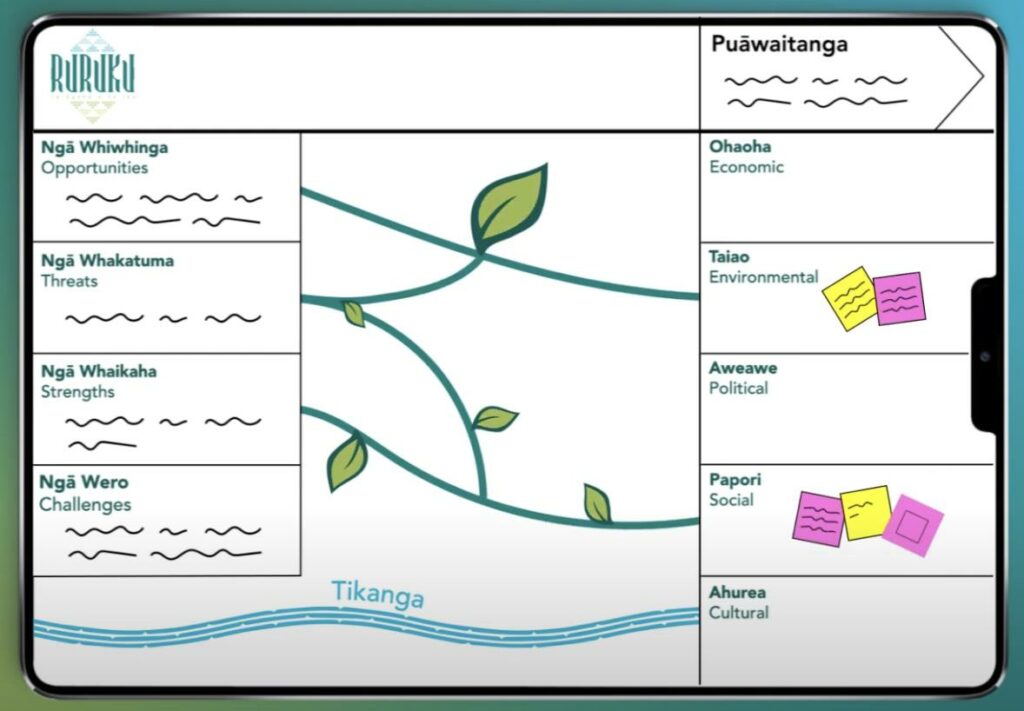

Here’s the Ruruku Canvas, the strategy tool. (You can see how the framework evolved in this short animation.)

The Ruruku Strategic Canvas

Here are the core features, in the order that people might use the canvas:

- In the upper right, pūāwaitanga is the guiding ‘north star’ to aim for: where we want our strategies to take us. Pūāwaitanga means “thriving” or “blossoming.”

- Tikanga, or values, are a stream running through the planning process and supporting the strategies.

- The left column represents where people are now, in an adapted ‘SWOT Analysis’.

- Below pūāwaitanga, in the right-hand column, are interlocking strategies for reaching our north star. These are cultural, social, political, and environmental as well as economic.

Some key changes were made from the original strategy canvas (below) to create the Ruruku Canvas. These included:

- Pursue a goal of thriving or pūāwaitanga (a gradual unfolding and blossoming). That’s better than a focus on ‘winning,’ the focus of the original canvas. Emphasizing winning “can make us try to compete with each other – we need to move beyond winners and losers,” a participant said.

- Every strategy should also be underpinned by tikanga (wisdom and values). This provides our “why”, and grounds our strategies in what is meaningful for our communities. In the final plan, Tikanga included “preparing for the future through intergenerational development and growth” and “Maori self determination to pursue a way of life that provides value and meaning.”

- The Ruruku Canvas emphasize ‘challenges,’ not ‘weaknesses.’ “When people define things as weaknesses, it’s like they’re our fault, and that’s disheartening,” a participant said. “Challenges are things in our way but we can overcome them.”

- The Ruruku Canvas shows how good strategies come from integration. It weaves together understanding of opportunities, threats, strengths and challenges, rather than having these elements ‘colliding’ as they did in the original Strategy Builder canvas (see below).

- Create specific places on the canvas for the other strategies that should underpin economic development. These are strategies related to culture, environment, politics, and social relationships. As one participant said: “Economic development is like snow at the top of this maunga (mountain) – without a solid structure that lifts us up, the snow melts away quickly.”

The Original Strategy Builder Canvas for Discussion

Developing a Regional Economic Development Strategy Reflecting Maori Views

Once people had designed the Ruruku Canvas, it became a framework for developing our regional economic strategy. That process happened over six months and involved people from across the region, ranging in age from 8 to 80. Working in teams, they filled in dozens of beautiful and insightful Ruruku Canvases with their ideas.

They identified hundreds of opportunities, threats, strengths and challenges; had great debate about pūāwaitanga, the ultimate goal; and found many strategies for achieving this goal.

From there, as facilitators, we identified key themes and provided draft strategies for consideration, critique and development in a further round of hui (town halls).

The Māori Economic Development Strategy— Ongoing and Multi-Layered

Ultimately, the Ruruku Canvas helped open up a strategic development to a wider range of people and views. It resulted in a Māori economic development strategy for our region, Wellington Te Upoko o Te Ika a Māui.

A new organization, Te Matarau a Māui, is executing the strategy. The organization’s name means

“the multi-faceted blade of Māui.” It’s a reference to the tool that Polynesian navigator Māui used to catch the giant fish that forms Aotearoa’s North Island. The emphasis on many blades or facets also reflects the diverse input into the strategy, and the “multiple strategies, programmes, and solutions” that will go forward.

New tools and types of information will support this approach.

Next Steps: Building out the Layers of Sustainable Development

One of the most important achievements of this effort has been broad acceptance of economic development as multi-layered. Economic development is sustainable — just and lasting — only if it is underpinned by cultural, social, and environmental development.

As the Te Matarau a Māui website states: “Although it is called an economic development strategy, in Te Ao Māori [the Māori world], all things are interconnected. A prosperous and well balanced Māori economy creates healthy whānau [families]; healthy whānau contribute to a thriving environment; a thriving environment forms the backdrop to a developing economy, and so on.”

One way to keep these important layers in mind is to show them in a map of the regional Māori business ecosystem. The image below sketches this mapping, now being done by Te Matarau a Māui. The important stories of the whenua (land) and its people are at the base (you can see the mouth of the fish). The physical landscape of the whenua is above that. More current social networks, institutions and stories are another layer. All these shape, and hold up, the economic development that takes place on the surface.

Prototype for a Layered Approach to Sustainable Development

This prototype was developed in association with design group ThinkPlace

The map will become a tool for visualization and analysis, so that it’s possible to zoom into a layer, find relevant data, and explore interconnections with other layers.

This method of economic data capture and visualisation will be up and running in 2024. Te Matarau-a-Māui is collecting data about Māori that has traditionally been stored in separate government departments, and are applying Indigenous data sovereignty principles to bring it into one place, controlled by Māori. This can lead to data visualisations, and development based on them, that are trusted by Māori to support holistic and sustainable development.

This kind of Te Ao Māori (Maori worldview) -led economic development is happening elsewhere in our region too. We see it in the development of companies built on indigenous/sustainable principles: for example, award winning culturally inspired tools for kids, and even on our university campus which puts Māori principles at its heart. It is possible to integrate principles like reciprocity, diverse forms of value, and a sense of place into any kind of organization (see a related article we wrote on these approaches).

Apply These Principles in Your Community or Organization

We hope you find inspiration in this story of community engagement, new strategy ideas, tools, and integrated development approaches. Here are some ways to apply these ideas in your location.

- Get involved in community planning efforts. As an individual or an organization, you are part of a community and have a role to play in dialogue (see NBS’s report on civic dialogue for more about the role of business). Dialogues might be convened by local government or community groups; they might touch on diverse aspects of regional development, from transportation to the economy.

- Be open in how you listen and engage. Often when working with communities, we find it easy to take a position of ‘helper’, positioning ourselves as someone who knows more. But if we enter situations assuming we know best, we limit the opportunity of others to show us what ‘best’ looks like for them. When you listen and engage deeply, then you can collaborate to meet the aspirations of a community, in ways that enrich both you and your community. We have started to work with private and public organizations in Aotearoa to help them integrate the Ruruku canvas into their strategic thinking, so you could do that too.

- Integrate some Indigenous insights into your own organizational planning. For example, weave together different types of strategy, or anchoring economic strategies to other kinds of development. You can also try going beyond focusing on winning and actually use or modify the Ruruku canvas. To support this, we offer a Miro Board version of the Canvas that you can play around with, enter your own strategic thinking onto it and even adapt the section headings to better suit your local community or organization (for example, a government agency we worked with wanted to change the heading of the ‘political’ strategies box to ‘voice’).

Too often, we may think that we don’t have options in how our world unfolds. Economic development models can seem clearly mapped out by established experts and out of our control. But different stories and ideas are all around us. The journey of the Ruruku Canvas and Māori economic development strategies like the one we have described show the potential for old ideas to have impact in new ways, for a brighter, more sustainable, future for us all.

Find Out and Do More:

Video shows development of the Ruruku Canvas

Video presents rangatahi (youth) perspectives

Access template of Ruruku Canvas you can fill in

Contact Jesse and Stephen – share your version of the Canvas!

Check out the website of International Academy of Research in Management and Organizational Studies Conference, running for the first time in August 2023, for further developing ideas in this area.

Add a Comment

This site uses User Verification plugin to reduce spam. See how your comment data is processed.This site uses User Verification plugin to reduce spam. See how your comment data is processed.