Sustainable finance has benefits for business and the planet. Find out what it is, why it’s important, and how to get beyond the talk.

By Dr. Hao Liang, Associate Professor of Finance, Singapore Management University

What is Sustainable Finance?

As someone who has been working on a field called “sustainable finance” for more than ten years, I keep hearing the question: “What is sustainable finance?” What is this approach that aims to make money and address social and environmental issues at the same time?

Is sustainable finance a new field within finance – a new way of dealing with money management, funding business activities, and creating investment products?

My answer: Yes and no.

Yes, sustainable finance is a new field of finance, with a new industry and new jobs, new regulations and frameworks developed by various governmental and nongovernmental bodies.

At the same time, it is still finance. That means that it still involves the fundamental elements of the field: capital allocation, investing, diversification, risk sharing, and value maximization.

Sustainable finance, however, provides a new twist on these fundamentals:

- Capital allocation decides how best to distribute an organization’s money. In sustainable finance, the goal is investing for long-term social and environmental sustainability.

- Diversification is the principle of spreading investments among different types of assets, to avoid losses. With sustainable finance, an investor may shift away from diversification for good reasons: for example, choosing not to invest in “sin stocks” like weapons or tobacco.

- Value maximization traditionally emphasizes financial value for shareholders. In sustainable finance, the goal is to also maximize the welfare of stakeholders – including the environment.

How Sustainable Finance Relates to CSR, SRI, and ESG

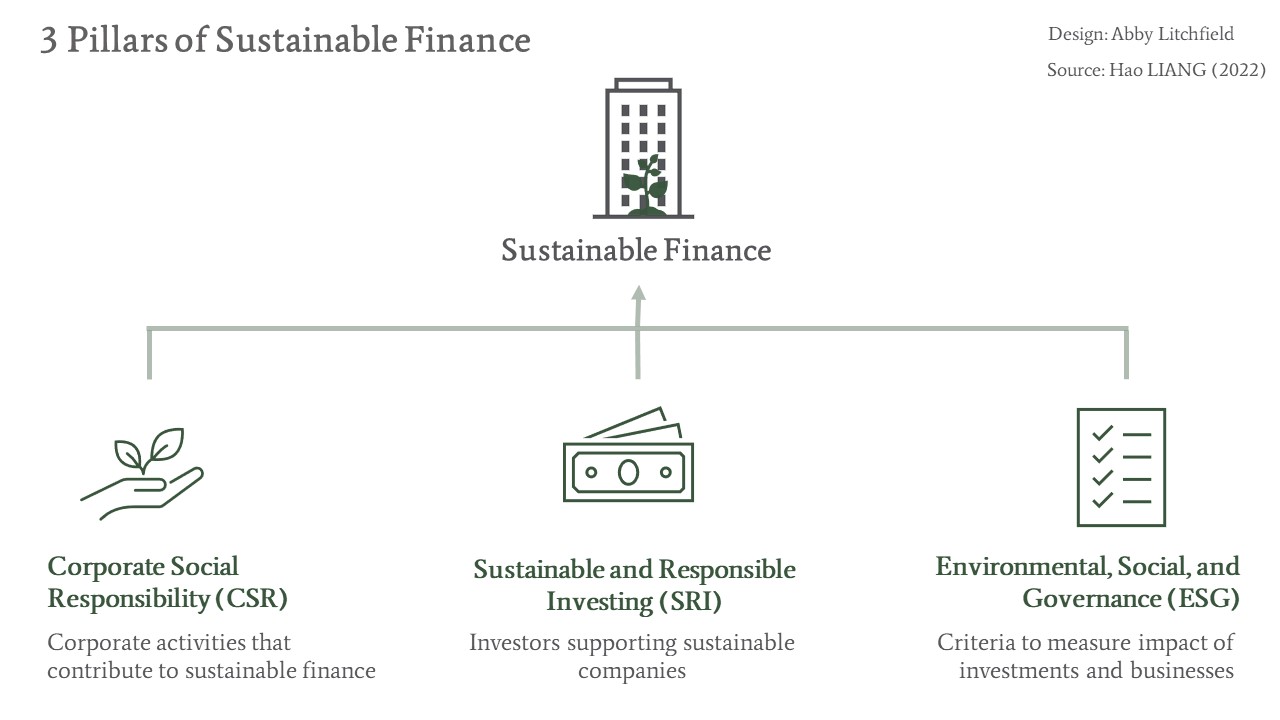

Here’s a more formal definition of sustainable finance, involving three terms you’ll hear a lot about: CSR, SRI, and ESG.

I consider sustainable finance as consisting of these three pillars or frameworks. These should guide the key actors in sustainable finance. To achieve the goals of sustainable finance, all actors — companies, investors, and policymakers — need to commit to these frameworks.

From a company’s perspective, sustainable finance refers to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR).

CSR refers to the set of corporate activities that improve human or environmental well-being. As a researcher in this field, I try to understand: Why do some companies actively engage in CSR whereas others do not? Do companies that do more CSR also enjoy greater profitability?

From an investor’s perspective, the key lens is Sustainable and Responsible Investing (SRI).

Through SRI, investors put their money into companies with good CSR activities. Institutional investors are leading in this area; these are mutual funds, pension funds, sovereign funds, insurance companies, banks and financial institutions, family offices, and corporate investors. Here, we need to understand: What are the motivations and return implications of SRI for investors?

For everyone — companies, investors, and policymakers — Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) data matter.

ESG quantifies and values CSR and SRI activities in order to show the impact of sustainable finance, created by business operation and investment. We are still trying to understand how best to measure ESG.

Here’s how these concepts relate: When companies care about stakeholder welfare, they engage in CSR. When investors put their money in businesses with greater CSR engagement, they make SRI. For both CSR and SRI, we measure them using ESG.

Why Is Sustainable Finance Important?

Sustainable finance is becoming a global trend and a mainstream business activity. We can see this in the action of companies, investors, and policymakers.

Almost all major listed companies, even those in the energy or mining sectors, have established CSR or sustainability departments, appointed chief sustainability officers, or have a CSR committee on their boards. They all issue annual sustainability reports to disclose their carbon footprints, community engagement, employee treatment, and various other stakeholder issues.

Most asset managers, especially institutional investors such as mutual and pension funds, claim to integrate ESG into their investment strategy. The numbers speak for themselves: According to the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, over USD$35.5 trillion was managed for sustainable and responsible investing globally in 2020.

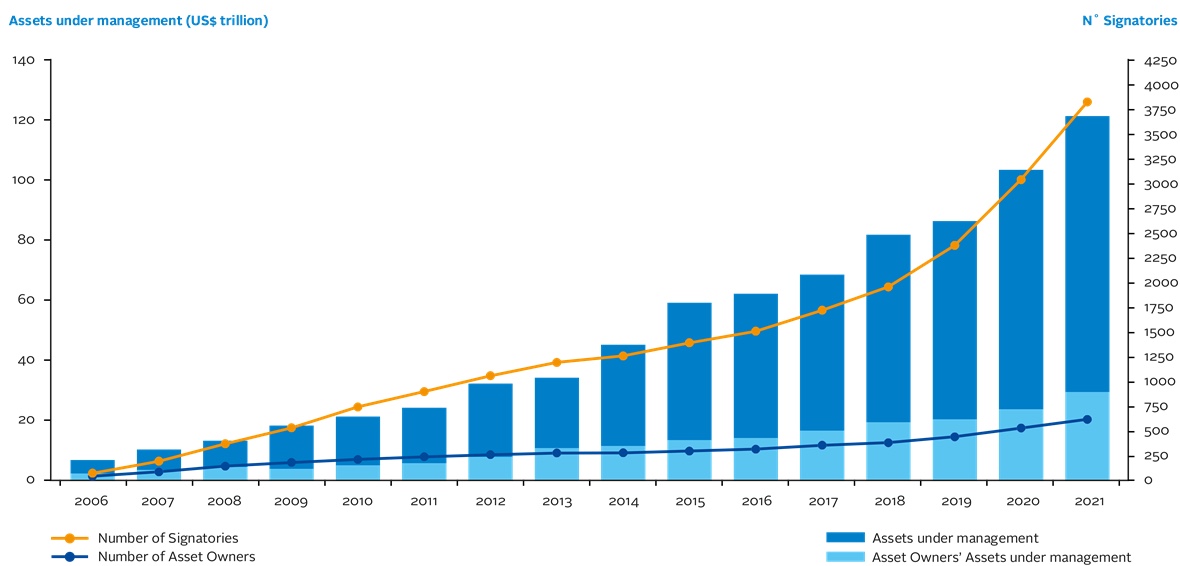

The United Nations Principles of Responsible Investment (UN PRI) has more than 4,000 signers collectively managing USD$120 trillion assets; signers include huge investors such as BlackRock, CalPERS, Calvert, and the Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global.

The figure shows the growth in support for UN PRI over time.

Policymakers are working toward the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), 17 global goals set by the United Nations in 2015, to be achieved by 2030. This also adds fuel to the sustainable finance fire. The goals include 169 detailed targets around social and economic development issues. To achieve the SDGs, we need trillions of dollars capital to finance different projects; where those projects have a financial return on investment, that money could come from sustainable finance.

Many other pressures are also driving sustainable finance. These include events such as international climate conferences (Paris Agreement, COP 26) and campaigns on board gender diversity by large asset managers (Black Rock, State Street and Vanguard). These events and movements are raising awareness of the importance of sustainable finance among corporations, investors, and the general public.

What Criteria Are Included in Sustainable Finance?

Today, almost every company and investor is trying to claim that what they do somewhat relates to sustainability. That’s because sustainability claims can often bring them significant financial benefits: lower cost of capital (because more people are willing to put their money into sustainable companies and funds), lower interest rates from banks (because banks perceive sustainable companies as having low risks), and greater capital availability.

Given the many claims, one may wonder how truthful they are. Indeed, one of the greatest challenges in sustainable finance is how to be sure whether an operation or investment is actually sustainable or simply “greenwashing”.

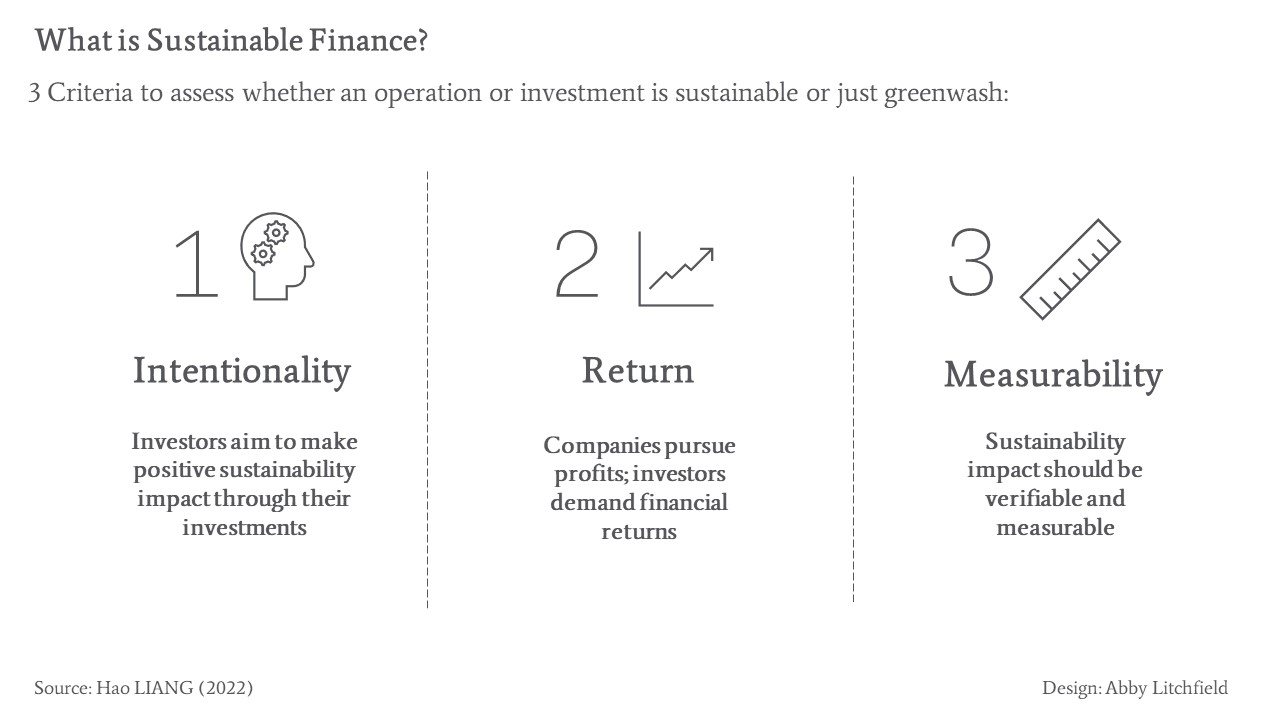

To me, three main criteria must be applied to determine what’s really sustainable finance. These are intentionality, return, and measurability.

Intentionality means that investors intend to make a positive environmental or social impact through their investments. This is especially the case for impact investing (usually done through private equity). Investors can be passively holding shares in sustainable companies or actively involved in the investee companies’ decision-making.

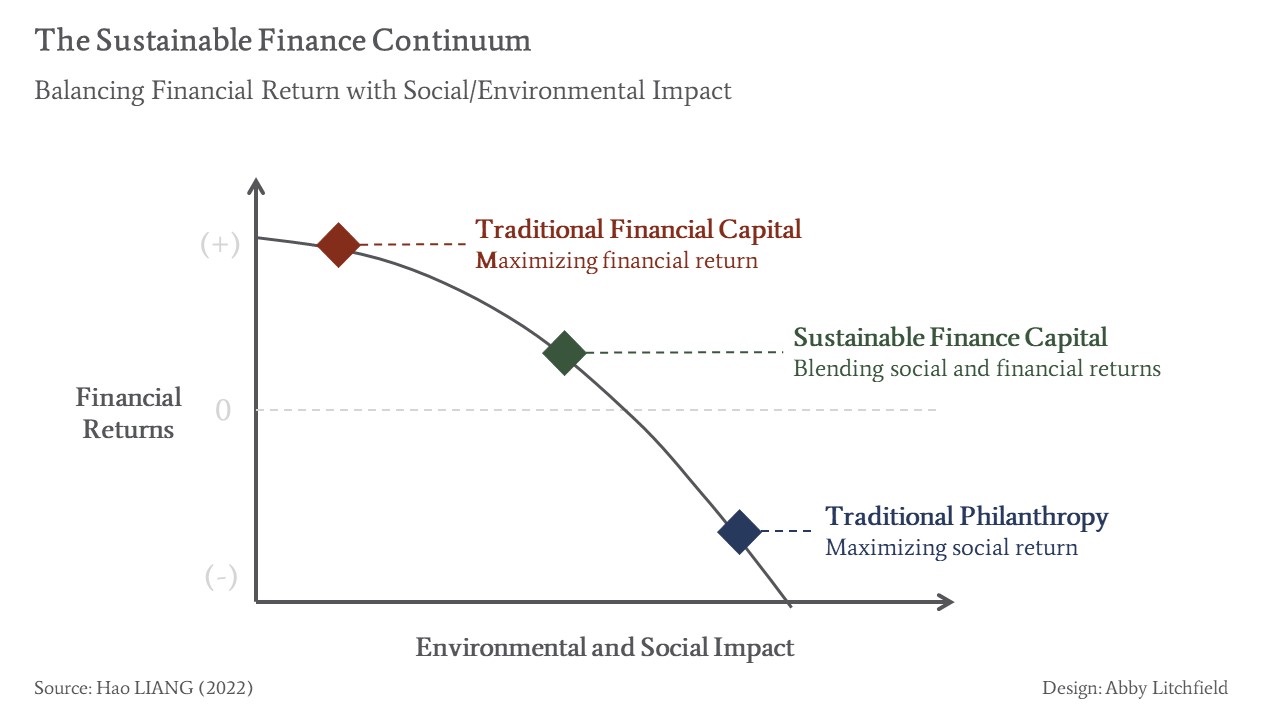

Return means that sustainable finance is still finance — companies still need to pursue profits and investors still demand for financial returns. It’s not philanthropy – but it does differ from traditional finance. Investors might accept a lower rate of return, for example, in exchange for sustainability impacts. The figure shows where “sustainable finance” fits between financial return vs. environmental/social impact.

Measurability means that the sustainability impact from a company’s operation, or an investor’s action, should be verifiable and measurable. Verified usually means that claims are independently assessed, e.g. by an auditor. Sustainability metrics should also be clear, meaningful, transparent, and capable of being compared to others.

Measurability Is a Challenge in Sustainable Finance

If you’ve explored the field of sustainable finance, you may have been confused by the many ratings systems and terms. Here’s a tour of the landscape and the issues.

Many third-party rating agencies – private and public – have developed ESG ratings, based on metrics, for managers and investors to gauge how sustainable a business or an investment is. But experts in academia and practice have raised concerns about these ESG ratings. The different ratings systems may not “agree” with each other or be transparent; they can be biased and inconsistent. Ratings systems have also focused on public companies, whereas the bulk of sustainable finance happens in other areas: private equity, projects, fixed incomes, etc.

In response, new standards and policy frameworks are being developed by international organizations, governments, NGOs, and commercial investors. These variously focus on carbon/ESG disclosure, corporate reporting, impact measurement, and portfolio evaluation. The chart shows the many available frameworks.

These include the Taskforce for Climate-Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD), Greenhouse Gas Protocol, EU Taxonomy, Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), Integrated Reporting (<IR>), Sustainable Accounting Standards Board (SASB), Impact Measurement Project, IRIS+, and many, many more.

But, perhaps because there are too many frameworks, managers and investors very often get confused about which one to follow.

Another puzzle is how to integrate different kinds of social, environmental, and financial impacts — so that the stakeholders can gauge what’s the “net impact” of an operation or investment.

There’s no easy answer to these puzzles – but there are many people working on them. The hope is that solutions – or better approaches – will continue to emerge over time.

Examples of Sustainable Finance

I can spend a whole day talking about different sustainable investing strategies. People have come up with a host of creative and even exciting approaches. I spend a lot of time talking about terms like ESG integration, negative/exclusionary screening, engagement and active ownership, norm-based screening, positive/best-in-class screening, sustainability-themed investing, green, social, and sustainability (GSS) bonds, etc.

But instead of diving into the jargon, I want to give two concrete examples of how sustainable finance can benefit multiple stakeholders, based on my own field study and teaching.

Music Securities

Music Securities is a Japanese financial institution that supports musicians’ economic independence. It created a crowdfunding platform, “Securite,” which helps musicians produce albums independently of major record labels.

Securite has extended beyond music, because of Music Securities’ social mission to promote financial inclusion through empathy-based crowdfunding. Now, it aims to help small and medium enterprises (SMEs) that aren’t served by traditional banks or venture capitalists, because of their location or perceived lack of profitability.

Once listed on the Securite platform, these businesses gain access to a large pool of retail investors across Japan. Securite connects investors and SMEs. Investors choose the businesses they want to invest in and can make as small an investment as US$100; they then receive a certain percentage of the business revenue. This model matches previously untapped sources of demand (from retail investors) and supply (from SMEs) to broaden the scope of impact investing.

Pay for Success (PFS) contracts/ Social Impact Bonds

Some social problems never seem to go away. Pay for Success (PFS) contracts, or Social Impact Bonds, find a new way to tackle them – with nonprofit expertise, private sector funding, and rigorous evaluation.

In a PFS initiative, private funders pay for an intervention; the government reimburses them only if a third-party evaluator determines that the initiative has achieved specific outcomes. For example: with the Massachusetts Juvenile Justice PFS Initiative, non-profit organization Roca worked with almost 1000 young men over four years. These men had been arrested previously; the intervention aimed to help them re-integrate into society.

Roca received funding for the project from a Social Impact Bond, supported by foundations and private sectors investors. If Roca’s services are proven to produce positive societal outcomes and savings for the State of Massachusetts, the government repay bond holders with up to $27 million in success payments.

Find Out More

Learn more about sustainable finance through the website of the Singapore Green Finance Centre, which I co-direct. We offer regular updates on sustainable finance news, webinars and panels, links to research papers as well as a host of research on different aspects of sustainability finance. Our goal is to be the leading resource for financial education and impactful research on climate change and environmental risks in the Asia region.

The Singapore Green Finance Centre is an initiative of Imperial College Business School and Singapore Management University, backed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore and leading global financial institutions.

About the Series

“The Basics” provides essential knowledge about core business sustainability topics. All articles are written or reviewed by an expert in the field. The Network for Business Sustainability builds these articles for business leaders thinking ahead.

Add a Comment

This site uses User Verification plugin to reduce spam. See how your comment data is processed.This site uses User Verification plugin to reduce spam. See how your comment data is processed.