Partnerships between organizations and Indigenous peoples can help reverse a history of oppression – but require deep relationships and trust.

For centuries, colonialism stripped Indigenous communities around the world of power and resources. Those centuries of oppression left lasting scars.

Indigenous leader BJ Cruse describes the impact of colonialism in Australia: “Our community has experienced devastating losses. They were forced off their lands and onto missions with no regard for familial association. Children were taken from their parents in attempts to assimilate them into settler society, where cultural practices and the use of language were often violently repressed.”

Trauma experienced in one generation can be passed down to the future generations, through behavioural and even biological changes. Colonialism also set up long-lasting systems of economic discrimination.

Today, persistent inequity between Indigenous peoples and white settlers also matters for Western organizations. Many companies find themselves working with Indigenous peoples on resource development projects, where they are challenged to consider long-ignored injustices. Others partner with Indigenous peoples as part of broader community development efforts.

Strong Partnerships Can Be Powerful

Partnerships between Western organizations and Indigenous peoples can deliver outcomes that are positive for both parties. For Indigenous peoples, partnerships may provide respect and recognition, and advance their community goals. Companies and other organizations may be able to advance corporate projects and create social impact.

But positive partnerships require strong, trusting relationships. They cannot be transactional – focused on immediate gain — or superficial.

In this article, we look at lessons from the Bundian Way project in New South Wales, Australia. It’s a 20-year partnership between the Eden Local Aboriginal Land Council (Eden LALC), an organization representing the Indigenous community, and more than 40 Western organizations, including business, government, and not-for-profits.

The project is turning an ancient walking trail into a place to share the region’s history and cultural significance, develop better intercultural relations, and grow a tourism-based economy stemming from cultural sensitization. Over time, partners have developed a business model, surveyed and registered the site, and found funding. They have also worked to build strong relationships.

Dr. Maegan Baker studied the partnership as part of her PhD research, which won the 2022 Ivey-ARCS PhD Academy Best Paper award. Here, she and Eden LALC leader BJ Cruse share lessons for Western and Indigenous partners. (See also our article on another important lesson from the Bundian Way Project – the perils of “efficiency culture.”)

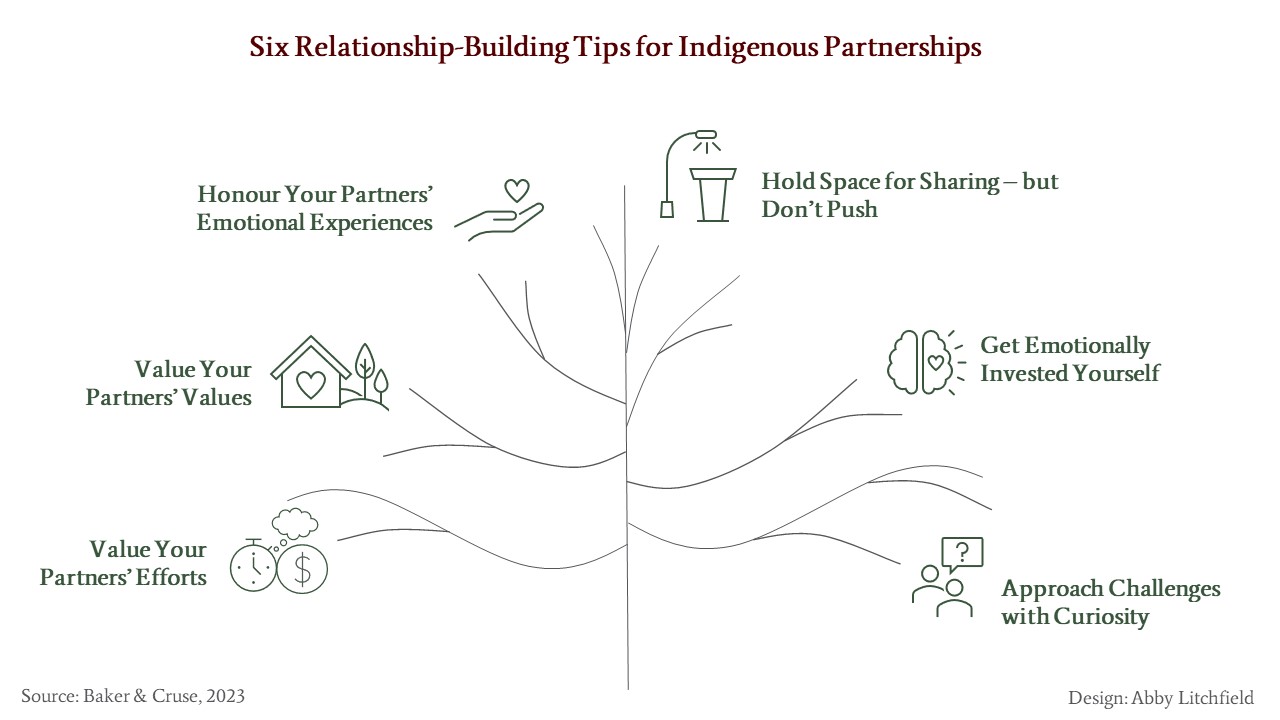

Tip 1: Value Your Partners’ Efforts

The Bundian Way project has been a lot of work. Much of the workload fell to the Indigenous partners, often in an unpaid capacity. Unpaid tasks included community liaison, project planning, and sharing cultural insights (which often require time to discuss within the community before sharing more broadly).

Much of this work requires Indigenous knowledge and therefore shouldn’t be done by Western partners. However, Western partners should recognize that Indigenous partners bear most of the work.

That’s especially unfair because the problems being addressed only exist because of the centuries of Indigenous marginalisation that Western partners benefit from today.

Western organizations should acknowledge and value Indigenous partners’ efforts. For example, Indigenous partners shouldn’t work for free when others are getting paid. When applying for grants, discuss how to quantify your Indigenous partners’ time so they can be paid for their work.

If everyone is working for free, recognize that your Indigenous partners are likely working full-time jobs and doing other community work, so things may take longer.

Valuing your partners is not only fair but incredibly important symbolically. You’re helping to reverse centuries of undervaluing and exploiting Indigenous peoples.

Tip 2: Value your Partners’ Values

Partnerships require considering both parties’ interests. They need to be mutually beneficial.

Indigenous leader Cruse has experience with another effort that didn’t recognize this truth. The Regional Forest Agreement, a negotiation in New South Wales, sought Indigenous support for Western organizations’ goals, but did not honour Indigenous needs and values.

The Eden Local Aboriginal Land Council, which Cruse chairs, supported the use of more land for logging, chipping, and national parks. In return, the government promised to give Indigenous partners access to their ancestral lands across the forest area.

The government’s promises weren’t documented — and they weren’t kept. The land promised to the Indigenous community was instead given partially to the National Parks and Wildlife Service, and partly used to build a Defence wharf.

Cruse describes the process as “insultation, not consultation.” That’s a view shared by many members of the Indigenous community.

The relationship damage caused when the needs of Indigenous partners are not seen and honoured takes decades to repair – if it can be repaired at all.

Tip 3: Honour Your Partners’ Emotional Experience

Many Indigenous peoples find partnerships with Western businesses extremely emotional.

Sometimes this emotion is positive. For example, delivering on community aims can improve an Indigenous partner’s sense of self-worth. In the case of the Bundian Way, building the trail has allowed the Indigenous community to take pride in telling their region’s story.

The emotional experience can also be painful. The partnership can trigger Indigenous partners to reflect on times their people were forced into changes, or where Western partners made and disregarded agreements, or where non-Indigenous partners were treated better.

Partnerships can involve sharing stories of intergenerational trauma. I Indigenous partners may help Western partners understand why the partnership activities are significant. The Bundian Way project, for example, is about building economic and social stability after a long legacy of stolen land, stolen wages, and stolen generations.

Finally, if the project outcomes aren’t what the partner hoped, it can negatively impact their sense of self-worth.

Western organizations need to recognise that these issues lie under the surface partnerships. If your Indigenous partner is sharing sensitive stories, understand that you are being trusted. In many cases, your partner is hoping you will want to do something about it.

You can strengthen trust by:

-

- Being patient

-

- Listening for the lesson

-

- Validating what the partner is saying

-

- Offering support where you have expertise

-

- (Most importantly) Following through on what you say you will do – or being clear about why you can no longer deliver so new options can be explored

Tip 4: Hold Space for Sharing, but Don’t Push

Indigenous peoples have long traditions of oral storytelling and sharing information, but may not share their motivations or stories with you right away – particularly if the partnership is new, or a topic is particularly sensitive.

Your relationship is a foundation that will allow you to hear Indigenous partners’ stories. Stories will come when you have demonstrated that you can be trusted, particularly since Indigenous partners are accustomed to not having their voices heard.

Relationships can’t be rushed, for practical and ethical reasons. Although you may have many questions, your partners may not feel safe answering them until your partnership develops.

Tip 5: Get Emotionally Invested Yourself

It’s easy to walk away from a partnership when the going gets tough. But in the Bundian Way project, many partners were involved for 5 to 20+ years.

Western partners’ emotions about the project enabled these long-term commitments. These emotions took many forms. Some partners were angry at the injustices the project was trying to address. Some partners felt guilt about the actions of their ancestors.

Partners also felt pride in project achievements and the impact it was starting to make at the community level. They had a strong sense of hope for a better future.

These emotions kept the partners involved, even when the work was challenging. If you are working in an Indigenous partnership, be ready for this emotional investment. Allowing yourself to care about the project is one of the best ways to support partnerships.

Tip 6: Approach Challenges with Curiosity

At some point, your Indigenous partners will probably say you are wrong, or challenge your views of the world. This may happen directly through words, or indirectly through body language.

Look out for these signals. These situations may initially make you feel defensive. Decide in advance to get curious. Ask to hear more about your partner’s views and to try to see the world through their eyes. Then, commit to looking for new solutions.

It’s also helpful to build your cultural and historical awareness early in any partnership. That will help you understand why Indigenous partners may not wish to follow some of your suggestions. It will also develop your compassion for your partners, strengthening your commitment to the partnership.

Many online resources offer a starting point. Some are listed below, but it’s also important to look for cultural awareness training specific to your region since all Indigenous cultures are unique.

-

- Cultural Competence – Aboriginal Sydney: https://www.coursera.org/learn/cultural-competence-aboriginal-sydney

-

- Reconciliation through Indigenous Education: https://pdce.educ.ubc.ca/reconciliation/

BJ Cruse’s Reflections: Changing the Narrative

BJ Cruse, Chair of the Eden Local Aboriginal Land Council, shares his thoughts:

The Bundian Way’s many benefits are an example of the deep benefit that can come from partnerships. This project protects an important Indigenous pathway, provides an outlet for Indigenous cultural maintenance, and creates eco-cultural tourism to enable better intercultural relations.

Perhaps most critically, The Bundian Way pathway shows how Indigenous peoples can support the good health and wellbeing of all cultures. This dispels stereotypes that characterize Indigenous peoples as detrimental or ‘taking away’ from society. Changing these attitudes is critical to improving the self-esteem of Indigenous peoples.

The contributions we are making through the Bundian Way allow people to see us and treat us differently, which fosters greater respect and trust between all of us.

Maegan’s Reflections: Becoming a Better Partner

Dr. Maegan Baker researched the Land Council’s “Bundian Way” partnership. She shares her thoughts:

Working with BJ, the Eden Local Aboriginal Land Council, and the Bundian Way Advisory Committee has been an experience that I will never forget. Over the past seven years, I have seen huge changes in how I engage with Indigenous partners – but also with non-Indigenous partners.

Now, by listening first, I now can generate a much broader range of collaborative options when faced with a challenge I don’t understand. In turn, the solutions I develop with partners are much better informed and much more resilient. When issues arise, I am better equipped to work through them in a way that seeks benefit for all.

I am immensely grateful for the opportunity to learn from and with them all. I know it will impact how I work and think for the rest of my career.

Find Out More About the Bundian Way

The 20-year partnership upon which these insights are drawn is called The Bundian Way. The project is in the community of Eden, in Southeastern Australia.For decades, Eden has struggled with local industries closing and fewer opportunities for training and employment. The psychological and economic effects have been compounded for Indigenous community members, who already suffer from trauma. Their attachment to the land also means that they also have a hard time relocating.

Indigenous elders felt that young people needed greater access to employment and support in being proud of themselves and their culture. “Indigenous peoples need to be able to be seen and treated as contributors to society,” says Cruse. Then, “they can feel they are contributors themselves.” This process requires participation from both Indigenous and Western partners.

The Bundian Way project emerged from this need. The Bundian Way is a 365-kilometre walking trail that runs between the Australian coast at Turebulerre (Twofold Bay) and the highest point in mainland Australia, Targangal (Mount Kosciuszko).

The ancient pathway has a rich history, travelled by many Indigenous communities for many thousands of years. The path was shared with early settlers, as they travelled from the sea to the highlands.

For more than two decades, the Eden Local Aboriginal Land Council (LALC) has been working to turn this trail into a cultural tourism opportunity. (Land Councils support Indigenous peoples in acquiring and managing land under the NSW Land Rights legislation.) The Bundian Way will educate tourists, community members, and visitors about the region’s history and cultural significance. It will also support business development such as guided tours, food experiences, art galleries, and accommodation.

Stakeholders involved include government, businesses, and the not-for-profit sector. The Bundian Way Advisory Committee provides support on challenges including funding, negotiating land agreements, developing business plans, marketing, and facilitating the ongoing use and management of the trail.

Add a Comment

This site uses User Verification plugin to reduce spam. See how your comment data is processed.Excellent contribution. Note importance of “seeing with two eyes” http://www.integrativescience.ca/Principles/TwoEyedSeeing/

Excellent contribution. Note importance of “two eyed seeing” from Mi’kmaw Elder Albert Marshall!

This site uses User Verification plugin to reduce spam. See how your comment data is processed.