International migration is part of our world. Businesses have a central role in managing this workforce.

We often hear that we live in a time of unprecedented mass migration. Looking at news headlines, you might think that there’s a dramatic rise in refugees escaping war, conflict, and climate change.

You might also hear that migrants are a drain on society – that they are unskilled, or require special services to adapt.

But are these accounts true?

“Migration has been politicized before it has been analyzed,” wrote analyst Paul Collier. International migration is a complex topic that draws strong emotions.

In this article, we blow away the myths of migration and identify the realities. We are scholars working on this issue with many others who care about what migration means for society and business.

We’re going to take a closer look at the facts, with a special focus on companies. How can they retain migrant employees and workers, and integrate them into company culture?

To answer questions like these, it’s important to understand how migration really works.

This means understanding large-scale migration trends – and misconceptions.

It also means recognizing the unique challenges and opportunities involved in working with different categories of migrants: high-skilled, lower-skilled, and refugees.

Migration Is Not New – But It Is Important

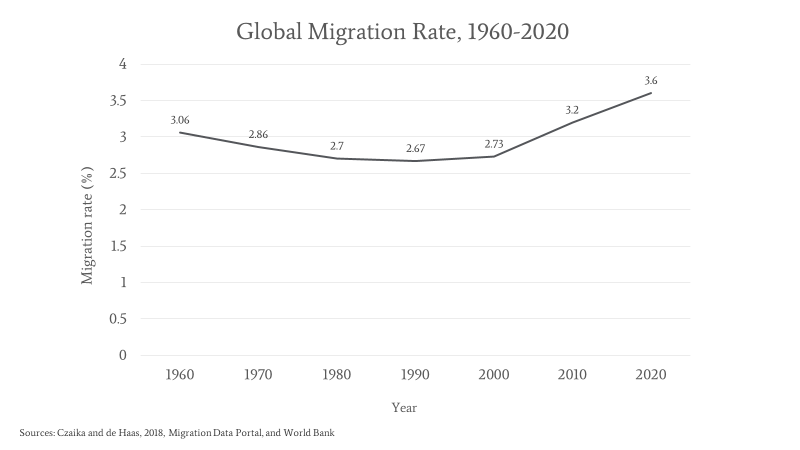

Despite the headlines, international migration is not a new phenomenon. Researchers Mathias Czaika, Hein de Haas, and colleagues report that migrants have actually remained a relatively stable percentage of the world’s population.

In the 1960s, international migrants were approximately 3.1% of the world’s total population. Over the next couple of decades, this number actually went down, to pick up again only in 2010. Today, the migrant total remains a very small percentage of the world’s total population, around 3.6%.

In other words, most people—nearly 97%— today continue to live in the country in which they were born.

Migrants are still a substantial population

Because the global population has grown fast, the absolute number of migrants is large. From 2000 to 2021, the number of international migrants grew from 150 million to 281 million. If all migrants lived in one country, it would be the fourth most populous in the world.

Migration can also seem striking because patterns have shifted in terms of who is emigrating where. For example, in the United States, the proportion of immigrants from Europe has dropped from 84% in the 1960s to below 20% today –immigrants now come largely from Asian and Latin American countries.

We agree with researcher Hein de Haas, that we need to start seeing migration as “an intrinsic part of economic growth and societal change instead of primarily a problem that must be solved.”

If global migration isn’t a crisis, can it be an opportunity? That’s the argument we make, for businesses and society.

As we continue the conversation: Here’s the definition for international migrants, someone who is moving or has moved across an international border, whether voluntarily (e.g., towards economic opportunity) or involuntarily (e.g., fleeing persecution).

Migration Benefits Business and Society

Why is migration so valuable?

For decades, businesses have been talking about the “global war for talent.” But today, we are facing more than that. We see a “global race for labour.” That’s the need for employees that shows up in the staffing shortages happening everywhere from your local coffee shop to your accounting department and company leadership.

The “race for labour” occurs because of demographic changes, like aging populations in many countries. There’s demand for both lower-skilled and high-skilled migrant workers.

Lower-skilled migrant workers are recruited widely in the global economy. For example, companies with production facilities in Thailand bring in workers from Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos. Those in Hungary recruit from as far as Mongolia and Vietnam. Even China’s cheap labor reserves are gradually depleting. Today, 1 in 20 lower-skilled workers worldwide is a migrant.

Value your supply chain? Lower-skilled migrants keep supply chains running, especially in geographically remote areas. They may staff warehouses, farms and factories on the outskirts of cities, freighters at sea, and jobs in construction, maintenance, and last mile delivery.

High-skilled migrants make up a critical proportion of today’s top talent, helping companies expand their knowledge, technical skills, and innovation. If you work in an innovative field, you’ve likely seen the contribution of these employees. Data show the same: The top 5% of inventors, as measured by the impact of their work, are five times more likely to be migrants than other inventors. Any international migrant has characteristics and experiences that can make them a powerful contributor. Here’s what research shows about migrants:

- They are more innovative, because of their international ties, language skills, and ability to navigate different cultures. They are literal trailblazers: “Immigration is pure entrepreneurship,” wrote LinkedIn Founder Reid Hoffman recently.

- They are better able to navigate across cultures, and can be particularly powerful in global leadership positions.

- They have greater “cognitive complexity” – they’re better suited for nuanced problem solving. Experiencing multiple cultures leads to more creativity and may boost one’s capacity to innovate.

Managers Need to Know How to Integrate Migrants

So: hiring migrants can be powerful. But integrating them into company structures and culture isn’t always straightforward.

For managers, it’s important to know that international migrants are a diverse group. Human resources needs can differ depending on what specific types of migrants your company is working with.

We’re going to look at specific tips for hiring and integrating three groups:

- High-skilled migrants

- Lower-skilled migrants

- Refugees.

We’ve already described the importance of lower- and high-skilled migrants. Refugees — who may be high- or lower-skilled – are also an important priority for society.

For High-Skilled Migrants, Focus on Retention

High-skilled migrants are clearly wanted by companies. But recruiting them is only the first step. Retaining them rests on how organizations integrate them, and that task can be challenging.

High-skilled migrants often feel “needed but not liked,” according to our research. They have high education levels and professional achievements. But after moving to a new country, they often experience a drop in social status because of their foreign education credentials and demographic characteristics (like certain ‘ethnic’ looks).

They face workplace discrimination and exclusion and spend considerable time and energy in coping with it. They told us: “We have to work 120% to achieve the same results as the locals” or “I had to run twice as fast as the local colleagues to just be at the same level field.”

This discouragement can lead them to leave organizations or be less productive. The solution is to implement human resources management practices beyond the standard supports (obtaining entry visas and work permits, onboarding training).

For example, companies can:

- Put equitable employment practices in place. They can invest in professional development for migrant employees, provide equal pay for equal work, and create safe ways for migrants to voice their concerns.

- Integrate differences. Find ways to appreciate different cultural views. That means cultural training for both migrants and local employees.

- Include migrant employees in decision making. Encourage healthy debate, and consider everyone’s ideas seriously.

- Provide support for migrant employees’ families. They can benefit from advice and practical help on accommodation, schools, language courses, and social networks.

- Recognize skills and successes. An international survey of 200,000 high-skilled employees by the Boston Consulting Group showed that their top priority was being appreciated by their employer.

For Lower-Skilled Migrants, Protect Human Rights

Employers recruiting and employing lower-skilled migrants face human rights challenges at every step.

Most work visa programs require that companies hire workers while they are still in their home countries. But not many companies have the capacity to dispatch recruiters to migrants’ countries of origin. As a result, companies usually rely on local agencies to connect them with these workers: recruiting them, managing passports, processing visas, conducting medical tests, and buying airfare.

Unfortunately, these intermediaries are infamous for unethical practices and corruption. They often charge individuals seeking a job abroad extremely high fees. A Central American guest worker legally entering the US may pay up to US$21,000 to obtain the necessary visa. In some Asian countries, migrant factory workers pay a recruitment fee equal to three years of their future salaries. Would you ever pay this much to get a job?

In many places, migrant workers are then mistreated in factories and dormitories. Companies may withhold identification documents, deceive workers about their contract, and threaten those who complain with deportation.

This may not sound like your company. But supply chains are notoriously opaque – and lower-skilled migrants are the energy powering supply chains.

Here’s what our research shows about how to address these issues.

- Know your supply chain. There are ways to illuminate what’s going on in your supply chain. Initiatives such as KnowTheChain, NGOs such as Verité and IHRB, and social sustainability consultancies such as ELEVATE offer guidance. (As a first step, employers should reimburse the fees that migrant workers pay in the recruitment process.)

- Put migrant management in your code of conduct. Be explicit about your company’s commitments. HP Inc. is a leader in this area: See their strict Code: “HP Supply Chain Foreign Migrant Worker Standard Guidance Document.”

- Attend to living conditions in migrant workers’ dormitories. Send company representatives or hire external auditors to visit migrant workers’ dormitories. Pay attention to sanitation, how many people are placed in one room, share bathrooms, how and what type of meals are provided, and if there is free technology for migrants to stay in touch with families back home.

- Install migrant worker helplines. Provide anonymous, reliable phone lines where migrant workers can voice concerns and grievances in their native languages.

For Refugees, Emphasize Flexibility and Resilience

Refugees are adapting to situations of great change. Employers may also need to be flexible.

In many countries, refugees historically have not had an immediate right to work, so companies haven’t seen them as a potential labor force. 2022 has brought unparalleled changes, as countries instantly issued working permits to millions of Ukrainian refugees fleeing the war.

For employers, refugee workers can lead to higher retention rates, increased diversity, and a strengthened brand and reputation.

Hiring refugees is also a meaningful way that companies can address global humanitarian crises. Hamdi Ulukaya, Chobani founder and refugee champion, describes the impact: “The minute a refugee gets a job, that’s when they stop being a refugee.”

Here’s how companies can effectively employ refugees:

- Be prepared to adapt your typical hiring practices. Refugee candidates may have gaps in their CVs due to asylum processes, or qualifications and references only from their home country. [Don’t hold these against them.]

- Use mentoring and buddy systems during the onboarding process. These speed up the integration into company culture. Here’s what a guide to refugee employment recommends: “An ideal mentor or buddy is someone the refugee can feel comfortable with asking questions, who is not a direct manager. Some companies use a ‘reverse mentoring’ program in which refugees mentor local employees about their cultural background and work experience gained abroad.” (Thanks to Betina Szkudlarek (University of Sydney) and colleagues for this guide.)

- Consider refugee employees’ immediate family members, if possible. Valued support can include assistance with accommodation, educational opportunities for children, and other community connections. When refugees are separated from their families, psychological and social support may be helpful.

- Learn about the impact of trauma. Refugees have gone through sometimes unimaginable experiences, and the consequences can be complex. Research shows that refugees’ experiences can be a basis for resilience and success, but also that trauma can emerge after years and even decades. (This is known as a delayed post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD))

Embrace the Potential of Migrants

For the authors of this article, these issues are personal. We study international migration and we have also lived it. Our experiences, as migrants, have included fleeing a war as a child refugee, moving across continents, landing in places where we don’t speak the language, working in lower-status jobs – like cleaning – and finally, ending with faculty positions. Hence, we personally know some of the challenges that migrants face, and some of the contributions that we can make.

We encourage companies to engage with the potential of international migrants. Be as brave as the people setting out on a new path!

Find Out More

Our website, “Migration, Business & Society,” offers resources from business toolkits, to the latest research, to inspirational art. See https://www.migrationbusinesssociety.net

About the Authors

Milda Žilinskaitė (mzilinsk@wu.ac.at) is a senior scientist and manager at the Competence Center for Sustainability Transformation and Responsibility, Vienna University of Economics and Business, and a visiting faculty at the International Anti-Corruption Academy. Her current research and teaching foci include labor migration, SDGs, ethics and value-based compliance. Although most of Milda’s career has been centered around academia, she is grateful to also have a personal history of low-status jobs as a migrant (including cleaning rabbit cages in Alabama). She is originally from Lithuania. See an interview with Milda on her migration experience.

Aida Hajro (a.hajro@leeds.ac.uk) is a professor of International Business and director of the Centre for International Business at the University of Leeds (CIBUL), and a visiting professor at the Vienna University of Economics and Business. Her current research and teaching interests lie in sustainable development, with special focus on the social-side of sustainability, specifically, migration. Aida is a child refugee from Bosnia. She wrote about her experiences in an article published in the European Journal of Cross-Cultural Competence and Management.

Add a Comment

This site uses User Verification plugin to reduce spam. See how your comment data is processed.This site uses User Verification plugin to reduce spam. See how your comment data is processed.